Map Irish Design researcher Elaine McDevitt recently presented at the National Museum of Ireland’s Women in Design conference on 25 May 2019 in Collins Barracks. Her paper took a look at women in design by analysingexisting figures in relation to graphic design and associated industries, such as Irish advertising, while balancing them against national statistics. She then translated the data and the approach of the industry itself to ascertain how socially constructed notions of masculine and feminine are echoed in the varying levels of women’s representation within graphic design. Here is her paper in full…

First, let me tell you a little about the Map Irish Design and what it hopes to achieve. With 2,379 pieces of work submitted we believe the 100 Archive to be the largest single dataset of Irish graphic design, ever. We aim to position and map this work within Irish culture, society and economics. Currently, we’re examining all of the work submitted to the 100 Archive since its inception — there are stories emerging and if you follow online you’ll hear more about these as they show themselves in more concrete form.

We’re exploring too, the studios who submit — where are they? What is their scale? What is their gender breakdown? How many freelancers are there? We’re examining ways that the data can be better captured in the future. In relation to gender, this will involve a less binary approach.

We are of course also looking to design initiatives and researchers that have previously grappled with some of these themes and their insights inform this paper. The definition of ‘design’ within available figures often varies and can include spheres as broad as engineering to craft. In keeping with the 100 Archive, the design industries I’m focussing on are graphic design and visual communications and to a lesser extent advertising, although as a larger industry, it’s extremely useful in providing us with very robust figures. It’s also useful because while advertising, as a genre, has long been held culpable for negative stereotyping, the industry has really begun to push back both with initiatives and with the type of work it produces.

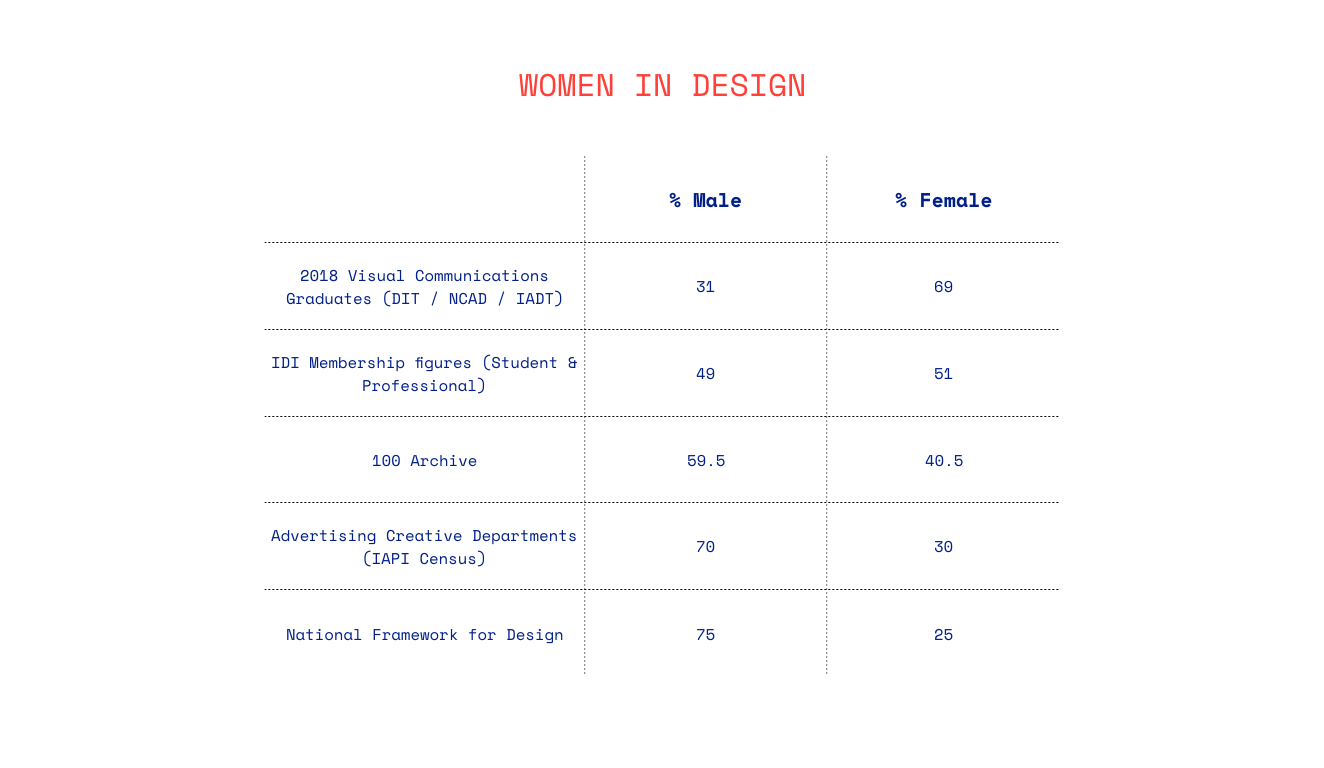

If we take a look at the figures we have available, we’ll see some interesting statistics:

- Graduates from Dublin’s three main graphic design courses last year comprise a 70% female to 30% male gender split.

- IDI membership figures which include student and professional members across graphic design, fashion, architecture and more show an almost 50:50 split. If we extract the student membership that is higher again at59% female.

- The 100 Archive shows a 60:40 male:female split. There will be questions we can pose in relation to this and as Map Irish Design develops we will be looking at the gender breakdown of company directors, freelancers and more.

- The IAPI census which examines advertising and media agencies shows us that while over 50% of the total workforce is female, the breakdown within Creative Departments is 70% male and 30% female. ICAD’s membership figures would reflect this and show a huge underrepresentation of women at senior and Creative Director level.

- The National Framework for Design in Enterprise in Ireland illustrates an even harsher divide at 75:25. For the purposes of ‘Defining the Design Footprint’ for measuring the economic contribution of design, this document includes figures from architecture, engineering, digital, advertising, ’specialised design’ (in which it places graphic design) and craft. Some of these areas have traditionally been very male dominated and might skew the figures slightly in relation to graphic design.

We know that the Irish graphic design industry, largely in line with International patterns, has developed and professionalised over the last 40-50 years. These decades have also seen the dissolution of the marriage bar in Ireland, several waves of feminism and massive improvements in employment equality laws. So how do the statisticscompare to employment figures in general?

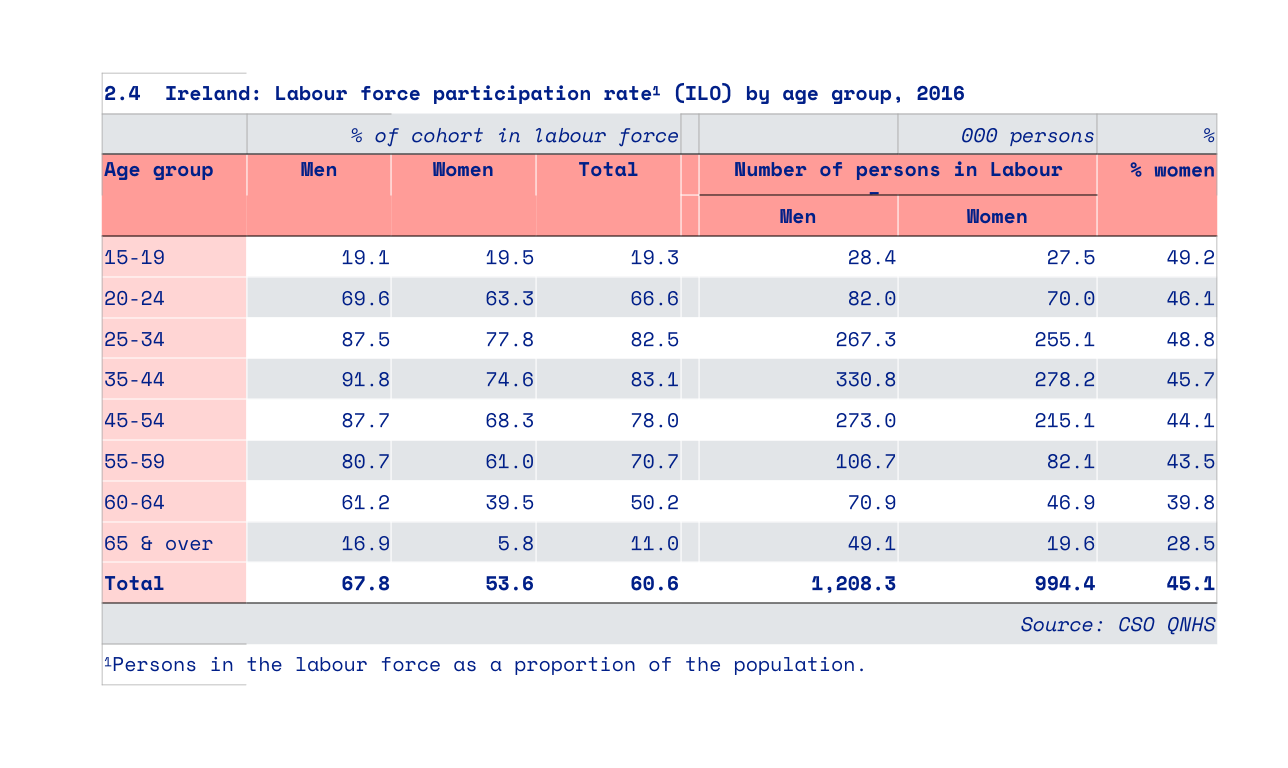

The CSO tells us that in the 25-34 age bracket, despite women reaching their peak level of employment, a gender gap of nearly 10 points is created (87.5% of men in employment, 77.8% of women). At 35-44 a wider gap forms with 91.8% of men in the paid labour force and 74.6% of women.In addition, the National Women’s Council of Ireland explains that while 46% of women over 15 participate in the workforce, they are much more likely to work part-time.Why?

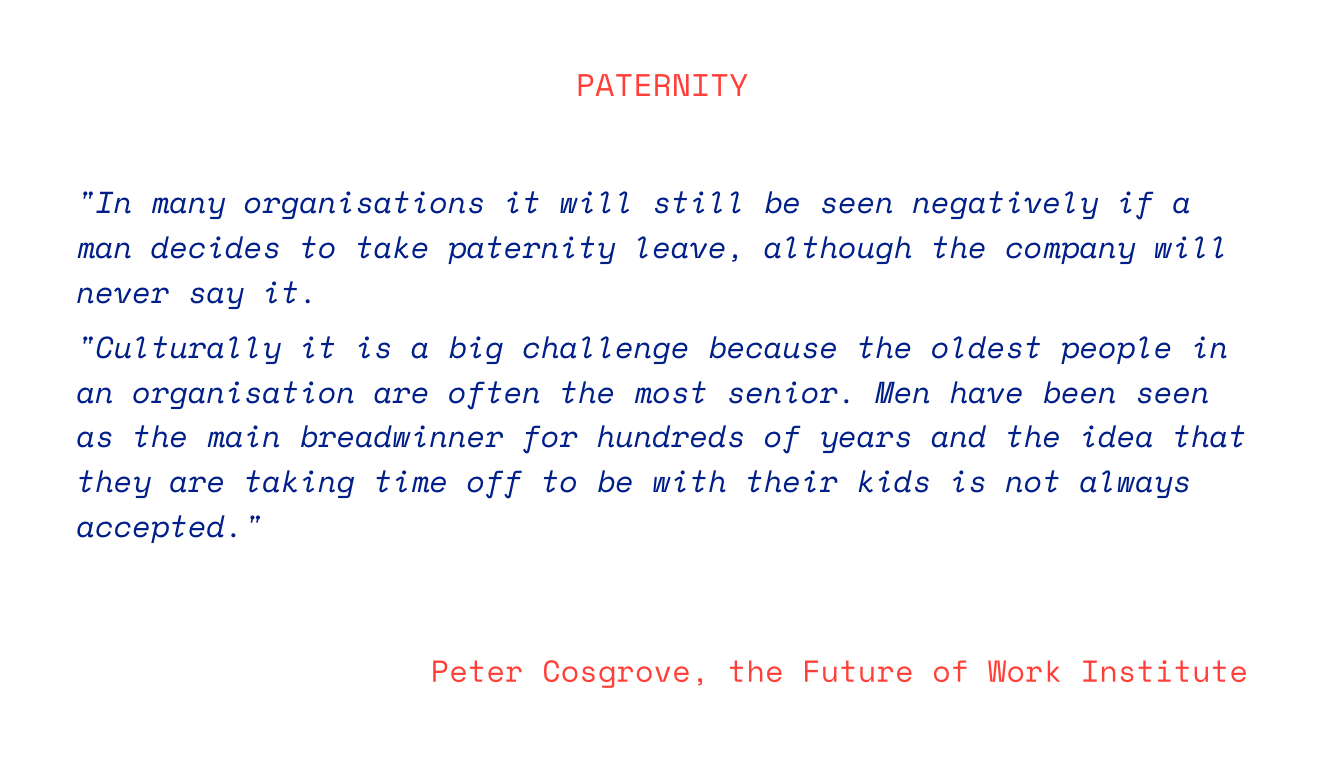

65% of all babies born in Ireland are to women aged between 30 and 39 and it is estimated 'that approximately 3,000 new mothers leave the workforce every year due to the cost of childcare’ (iReach Insights, “Baby Brain Drain research, on behalf of Citrix”. Press Release. 2015). Further to this, a return to work after maternity leave is currently being hindered by a lack of availability of childcare places since the introduction of the second ECCE year. This has led to many childcare facilities closing their baby rooms. Simultaneously, fathers are not taking up paternity leave at expected levels and the number fell by a further 10% in 2018. Peter Cosgrove, a recruitment consultant and founder of the Future of Work Institute states "Men have been seen as the main breadwinner for hundreds of years and the idea that they are taking time off to be with their kids is not always accepted.”

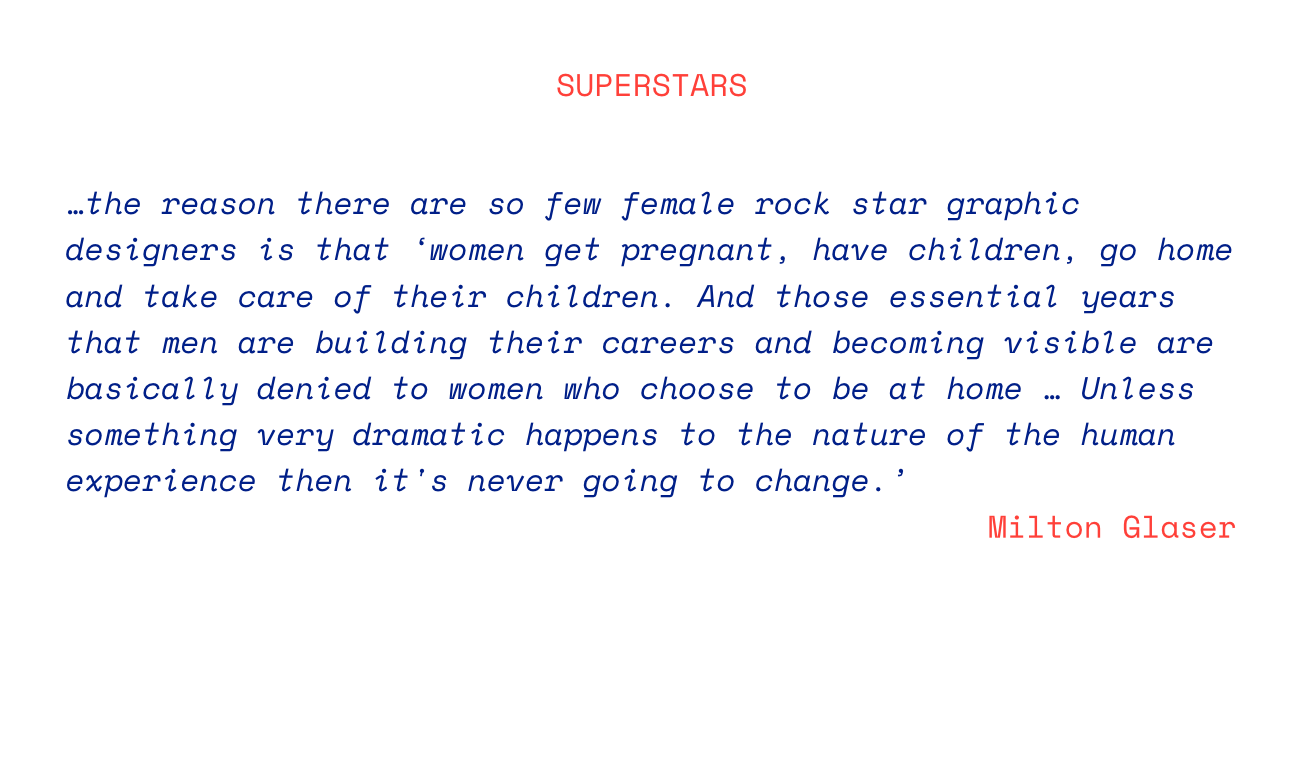

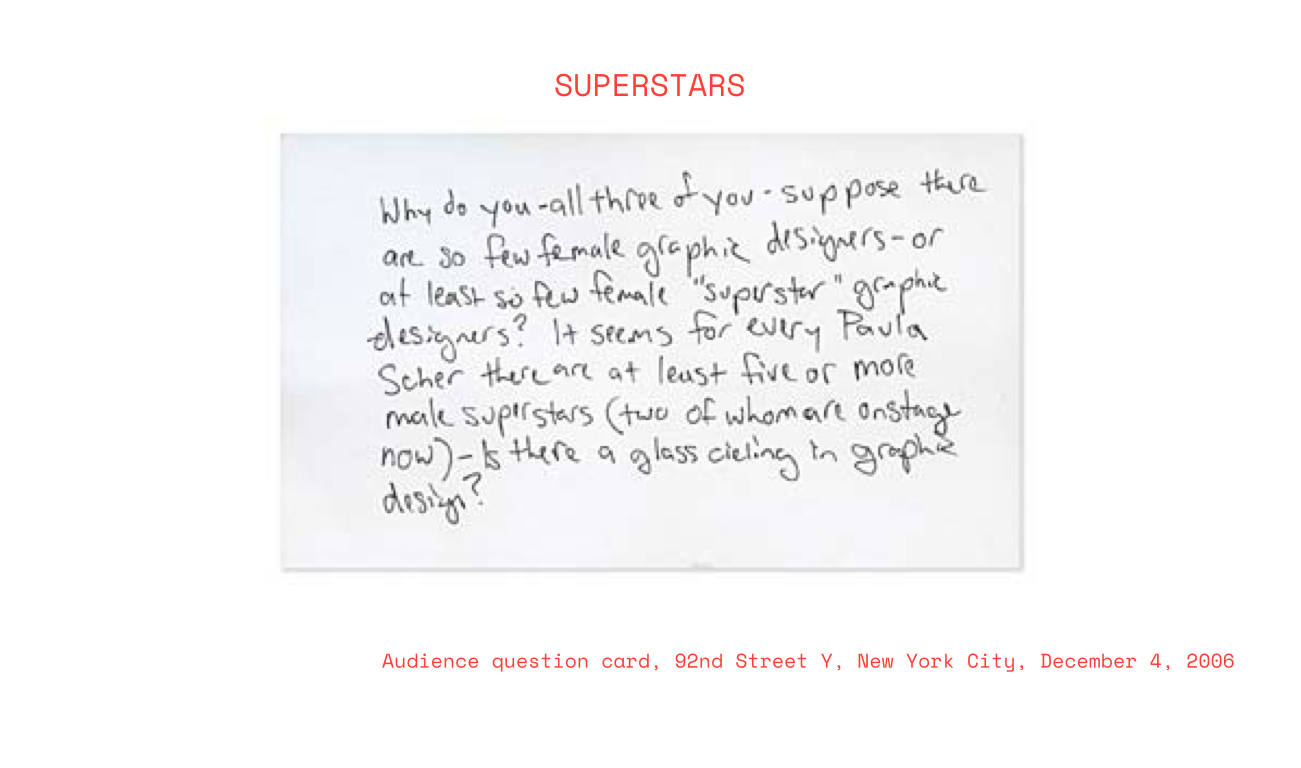

These figures, and the fact that 'women are 25 times more likely (than men) to look after their home and family’ leave us in little doubt that child-rearing is the primary reason women drop out of the paid workforce between the ages of 25 and 44. It is clear that motherhood, rather than parenthood is influencing the labour force, or, as Milton Glaser controversially put it in 2006, ‘women get pregnant, have children, go home and take care of their children. And those essential years that men are building their careers and becoming visible are basically denied to women who choose to be at home’.

Apparently this comment was met with several gasps from the audience but there is truth in it and it spreads across all industries. The biological fact of childbirth means that women require maternity leave, the risk is that this, along with other factors, can lead to discrimination or non-conscious bias against women not only when hiring and promoting for more senior roles, but in pay scale and the mentoring and training women receive within a company. In the UK, Creative Equals’ Equality Standard shows that creative women are 30% less likely to have any training, are not given the same quality of feedback as their male peers and are less likely to get access to key assignments. The fact that maternity leave often occurs during key career-building years can very definitely put women at a disadvantage compared to their male counterparts. The figures in design are more drastic than national statistics however, with a flip from 70% of graphic design graduatesbeing female, to the reverseat senior level.

So if we pick apart Milton Glaser’s comment in relation to the design industry, there are a couple of interesting points — the first is whether women do indeed ‘choose’ to stay at home. The National Framework for Design in Enterprise in Ireland shows that only 10% of the design workforce works part-time, compared to 23% of the total workforce so is this industry less adaptable to the working needs of parents than others? Are graphic designer mothers being forced towards other industries or other areas or towards freelance roles? What other factors are at play?

Secondly, the specific question that Milton Glaser was answering relates not just to female designers but to Superstar female designers - celebrities - and that brings us nicely to a cult of personality within creative and designer roles.In Advertising Cultures, Sean Nixon discusses ‘the distinctly masculine set of attributes associated with the figure of the artist, which had deep roots within the cultural milieu and beyond’ and identifies several creative directors known to cultivate ‘the attributes of the difficult artist’ and ‘flamboyant public profiles’.

A 2015 Duke University study led by Devon Proudfoot found that 'beliefs about what it takes to “think creatively” overlap substantially with the unique content of male stereotypes, creating systematic bias in the way that men and women's creativity is evaluated’. The study 'suggests that when people think about “creative thinkers” they tend to think of characteristics typically ascribed to men but not women, including qualities like risk-taking, adventurousness, and self-reliance'. Proudfoot concludes 'In suggesting that women are less likely than men to have their creative thinking recognized, our research not only points to a unique reason why women may be passed over for corporate leadership positions, but also suggests why women remain largely absent from elite circles within creative industries'.

Back in 1986, design historian Cheryl Buckley asserted that the 'practice of defining women's design skills in terms of their biology is reinforced by socially constructed notions of masculine and feminine, which assign different characteristics to male and female' (Design Issues, Vol. 3, N. 2 (Autumn), The MIT Press, Cambridge 1986, pp. 3-14) and this is still echoed in the varying levels of women’s representation within certain roles — IAPI’s figures break down the industry by role or department and show 65% of those employed in account management and a whopping 100% of PAs and secretaries are women whilst 70% of creatives and 65% of those employed in digital are men. 72% of board directors are also men, although this is a figure that has significantly improved in recent years, down from 82%.

Could there be a similar breakdown within graphic design? Do the socially constructed notions of masculine and feminine and the deliberate and masculine image of the ‘artist’ simply makes senior creative roles less attainable for women, who through centuries of gender conditioning have been taught to be the minders, the organisers and the mammies? Could qualified female designers be moving from creative roles into more care-giving or supporting style roles like account and project management within the industry itself? None of the figures we currently have can confirm this but it would certainly be interesting to pull apart some more to find out if the data might support such an assertion.An even larger discussion might be the value placed on the varying roles within the industry and how they relate to the gender pay gap, but that’s another paper entirely...

The work done by the 'Let Toys be Toys' campaign reveals evidence of stark gender conditioning in toys and clothing for children: boys are bosses, they get into trouble, they have battles and adventures and power. Girls are good. They like glitter and sparkle and friends, magic and fairies. And this reflects itself in the creative industries - creativity is reserved for the rule-breakers, the risk-takers — and who have we raised to be this way?

Thankfully, there is a lot of movement in this area — discussion is the first step, it challenges us all to think about the issues. There are also lots of initiatives and programmes that tackle gender diversity and bias head on. Locally, IAPI have introduced an Inclusion Network which examines the positive effect diversity, in all its forms, has on business and creativity, they have elected ‘Inclusion Allies’ to act as ambassadors within agencies and studios, as well as hosting events like Non-Conscious Bias training, hugely important for us all. In addition, they have introduced peer-support networking in the form of ‘While you were out’, focussed on women returning to the workplace after maternity leave. ‘Why Design?’ was developed by Kim McKenzie Doyle as part of her IDI presidency to address gender imbalance in the industry by profiling influential female designers and to inspire female second level students to join the creative industriesThere are plenty of programmes run internationally too but Creative Equals is worth a particular mention, and worth looking up.

In summary, we can see that the existing figures in relation to graphic design appear starker than the national statistics, particularly in relation to senior creative roles. In addition to women leaving the workforce for childcare reasons, there are additional and unique factors at play - the social constructs of masculine and feminine might just undermine the very notion of female creativity and how the industry approaches it, whether consciously or not.

Nonetheless, there is a noticeable sea-change and a concerted effort to address gender balance within the industry. There’s a way to go yet, a long way, but to wrap up and bring things back to the 100 Archive for a second, as well as the Map Irish Design project, which aims to communicate the impact of design, let’s remind ourselves of how creativity and design can be a force for good and a catalyst for change. Here are a few pieces announced as part of the 2018 Archive:

If you’d like to contribute to the project in any way, just get in touch. Thank you.