First published in the American Neptune in April 1944, the essay ‘Fluid Geography’ was written by design maverick, visionary and activist, Richard Buckminster Fuller. In Fluid Geography, Fuller discussed, among other things, the generic differences between the Landsman and the Seafarer. Fuller believed that the most significant developments in scientific knowledge were a direct result of the experience of sea travel and the desire to reach new shores. The Seafarer had to develop solutions to a different set of challenges than the stay-at-home Landsman: the ability to harness the wind, to navigate by the stars and continuously improve the ability of ships and their navigational instruments to cope with the dynamic environment they were working in. He claimed that it was due to these factors that technology advances far more rapidly at sea. He describes how, to the Landsman, ‘East’ and ‘West’ are stagnant locations to visit, but to the Seafarer, ‘East’ and ‘West’ are directions in which they may move, processes rather than events.

The Seafarer views the world from the outside; they ‘come upon’ the land, seeing the world from a comprehensive viewpoint, while the Landsman is restricted by the limits of their own personal horizon. With this in mind, and while acknowledging how technological advances have shifted the landscape of the industry in the past few decades, I propose contemplating how the graphic designer has advanced from the role of static Landsman, to active Seafarer. We have embarked on an exciting and adventurous voyage in a dynamic environment of our own. Our world is in flux, our tools constantly evolving — we are operating in a liquid state.

I use this analogy to help visualise where we have been, where we are now, and where we may go from here. Graphic design was once a more linear discipline, a land-based activity focused on talent, technique & rigour. Solitary designer as commercial artist, called upon at the end stages of a client process to make something happen from the confines of their desk space. Advances in technology, networks and access have allowed us to delve deeper, actively researching, investigating, discussing and collaborating, all the while responsive to the world around us. Graphic designers have evolved to become multidisciplinarians in a non-linear field — We are at Sea.

It is at Sea where we must draw on everything we know, in order to venture optimistically into the unknown. In this new role as Seafarer we are in exciting territory, exercising our inherent dynamic sensibilities, collaborating in teams, with a lack of hierarchy and a democratic spirit. In this move away from pure visualisation, we are adaptive experts. We are agile and shape what we’ve learned to new situations. No longer simply ‘making something happen’ we are now also identifying what needs to happen and embarking on iterative processes to realise it. Our goal at Sea is not to create a certain type of design, but a certain kind of evolution in design intelligence. Design as a way of thinking, an attitude, that can be channelled through multiple roles. Designers are working together in an interdisciplinary way while also engaging with industry, demonstrating a multifaceted skill set, and expanding their role to suit various needs. In any given context, designers are researching, investigating, writing, curating, making, directing, publishing, developing, archiving, agitating, producing. It begs the question whether designer is a big enough term to cover it all anymore. None of this would be news to Buckminster Fuller though. As a practising architect, systems theorist, author, designer, inventor and teacher, he coined the term ‘Comprehensivist' as a way to introduce himself. I am wondering if we might need to start doing something similar.

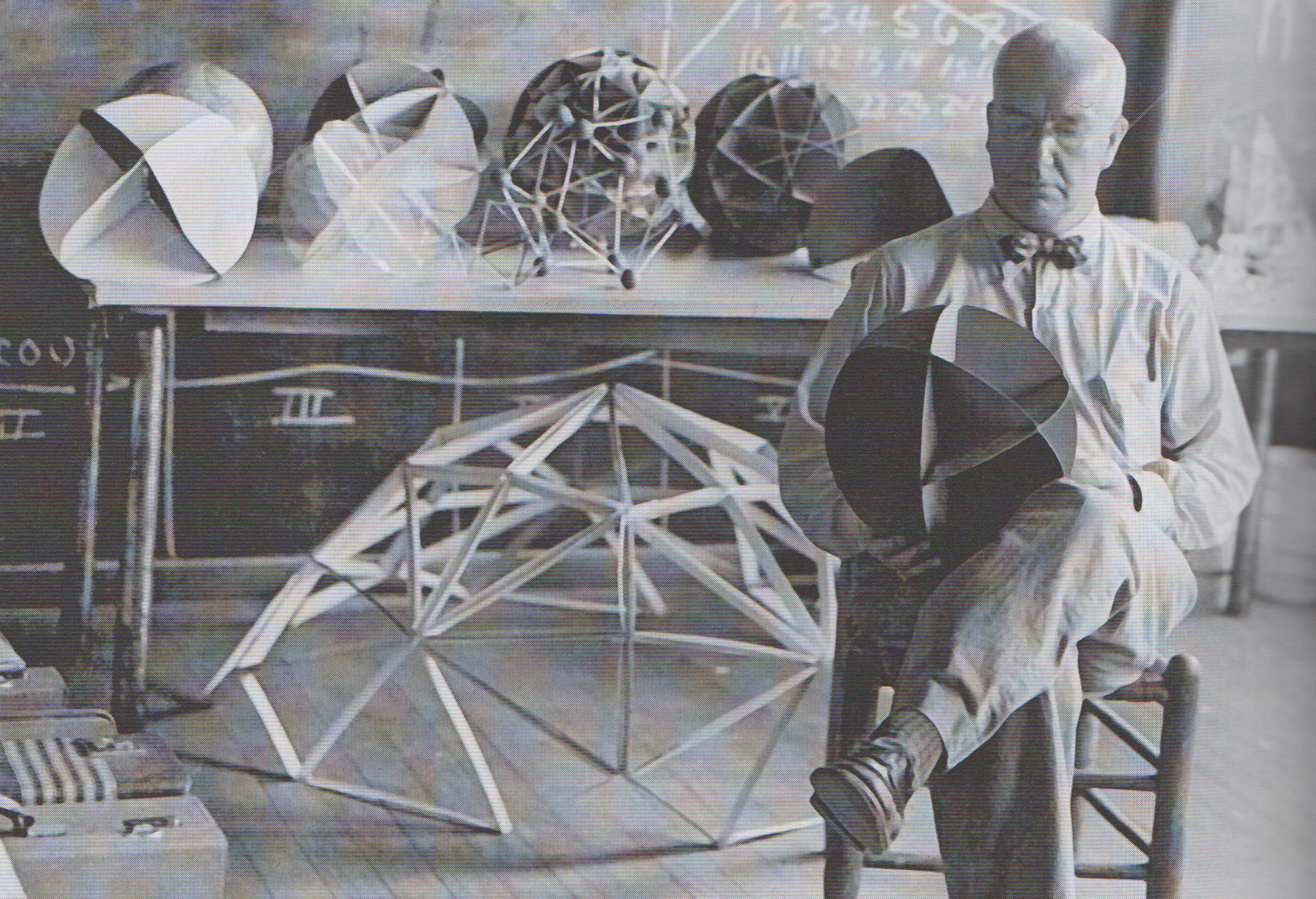

Kate Brangan is a practising designer, an educator at NCAD and one half of riso print studio Or Studio with Jo Little. See her profile on the 100 Archive and visit her website. Image of Buckminster Fuller at Black Mountain College, summer 1948, photographed by Hazel Larsen Archer.