The working dynamic of a freelance designer is hard to define. It varies from temporary in-house support, to working after-hours, to operating as a one-person studio. Oscillating on the edge of ‘employee’ and ‘employer’, freelancing is a middle way which bypasses the two extremes in a move towards working life salvation. I caught up with three Irish designers virtually — Eva Hogan (New York), Brian O’Tuama (London) and George Beattie (Berlin) — to learn how they navigate the intricacies of freelance life, how their work has been affected by the global pandemic and to hear about their plans for navigating the future.

The varied paths to freelance design

With nearly ten years’ experience as a designer at American superbrands like Teen Vogue and Kate Spade, Eva Hogan transitioned into the freelance world armed with a praiseworthy reputation and first rate know-how. Following a nationwide campaign for Target USA via Chandelier Creative, Eva landed work with ad agencies like Mythology and Laird & Partners and brands like Daily Harvest, without the need for an agency leg-up. For Eva, freelance is the next evolution of an established career; it’s an opportunity to sharpen her focus as a Creative Director.

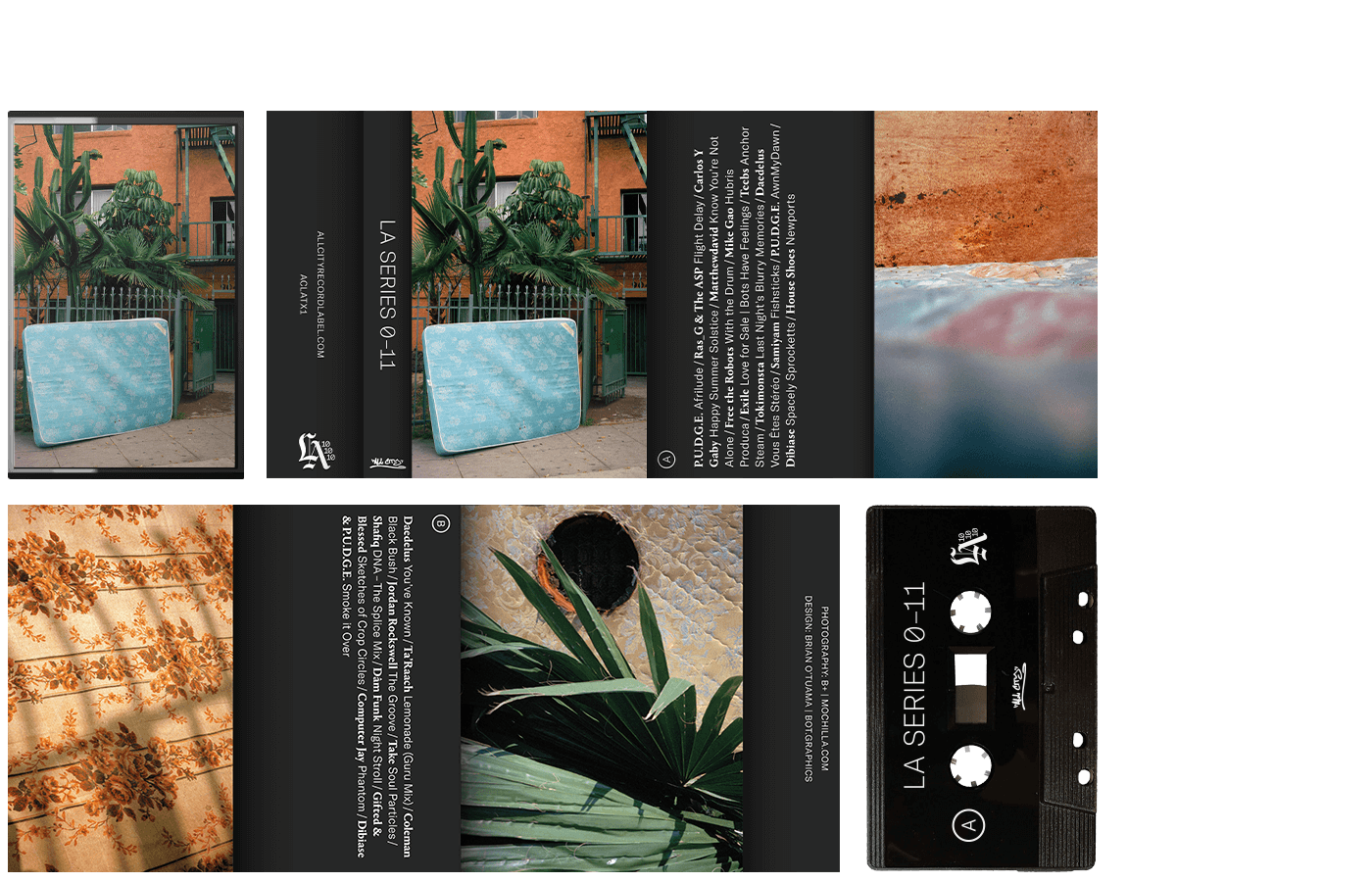

In Brian O’Tuama’s case, he began freelancing soon after graduating, following a stint at Dublin-based studio AAD. After moving to London in 2016, he juggled in-house freelance work arranged by Represent. “I would be transplanted in different studios on a project by project basis,” says Brian. “It was a good way to get the lay of the land in a new city and to snoop around other people’s offices. It made me realise how little desire I had to work in many of those kinds of studios for any length of time, let alone the rest of my life.” His rented East London studio (shared with 100 Archive ‘In The Making’ interviewee Dave Lawler) facilitated a departure from agency work in 2017. Located above an unlicensed nightclub and next to a Jamaican social club / recording studio / weed shop, the “paper thin” walled room became a gateway for cultural events, parties, and patrons, leading to new music-related work and connections — an industry which has become increasingly central to Brian’s work.

.png)

.png)

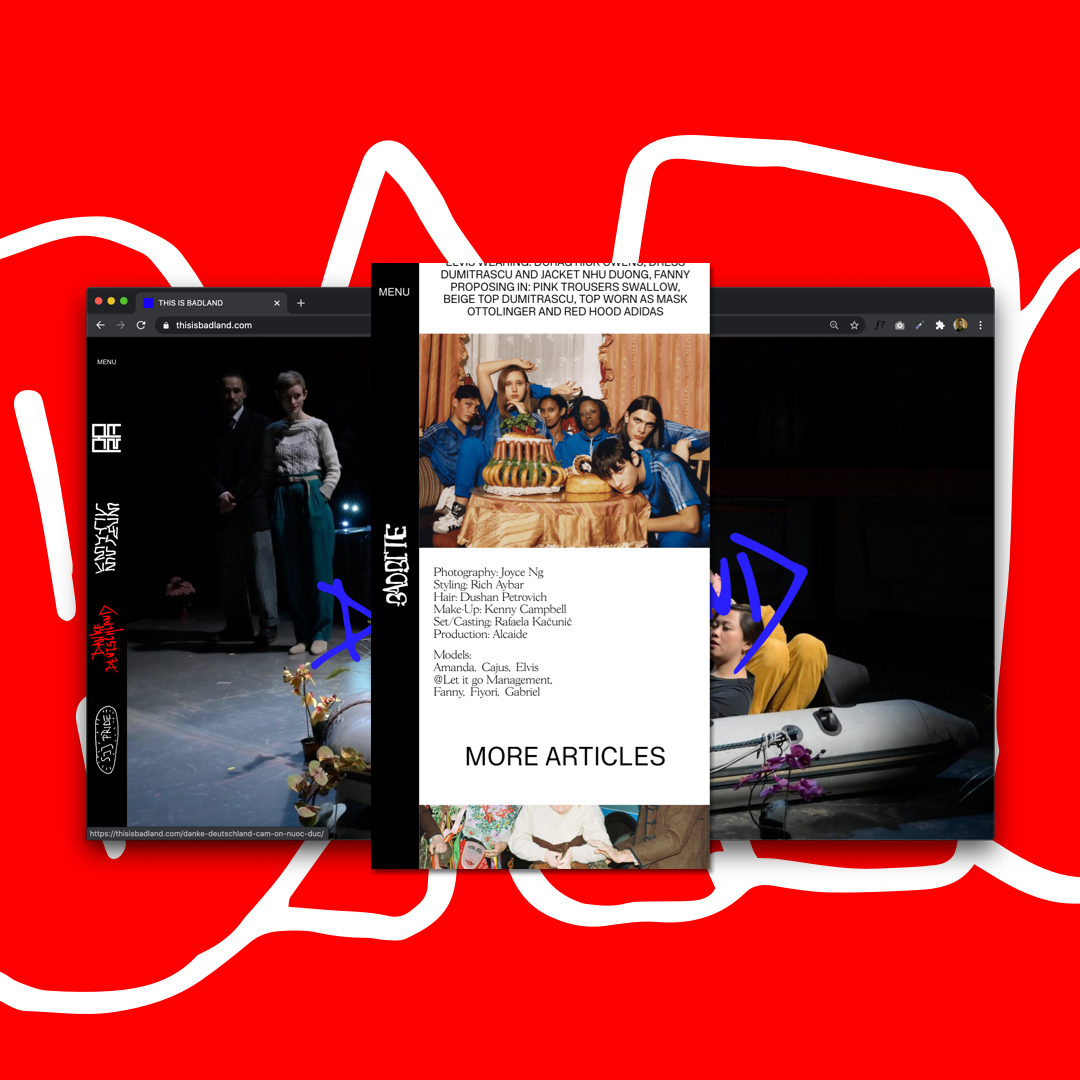

For George Beattie, mixing in-house contracts with freelance work naturally leads to the next job. His weighty foundation of Dublin-based projects at Indigo & Cloth, working with clients like The Teeling Whiskey Company and The Dean Hotel Dublin, gave George a foot in the door in Berlin, where he has since secured projects with Badland Magazine, Dittrich and Schlechtriem Gallery, and ENAU Records to name a few. “The beauty of being a freelancer allows you to connect with people and their stories in an exciting and novel way” says George. His perspective on what has been mainly a freelance career so far, is reminiscent of the ups-and-downs aptly consolidated in James Tupper’s 2019 animation entitled 'Freelance'. George is now based full-time at Carhartt-WIP Berlin (a division of the American workwear company) and takes on the odd freelance temptation when the project fits.

Picking priorities

Freelance designers tend to find their own way of managing the trials of self employment and how to handle pricing, budgets, tax, etc. Simply, every design project starts with a time estimate; to define the scope of work and plan for any future revisions. Eva, Brian and George prefer to charge a fixed day rate, rather than an hourly rate, and estimate timelines based on that. Their projects are then billed at 30–50% before starting any work, to set a precedent for the client–designer relationship.

Despite these time estimates being a well intentioned guess between best and worst case scenarios, inevitably deadlines become stretched and final, signed-off artwork regresses to work-in-progress. Committing to a freelance project means committing to shifting timelines. When projects can unexpectedly bleed into weeks, as a one-person show, a freelancer must be selective from the offset. In George’s words, “the freelancer has the power and autonomy to pick and choose”.

What are some tactics for creating an ideal working situation? While designers are adept at presenting others to the world, often the same cannot be said when it comes to marketing themselves. With uncertainty on what is most effective — a pristine portfolio, good word of mouth, or being just generally sound — our three designers have similar approaches to attracting better work.

“There are lots of ways to have a personal brand — through your work ethic, the way you treat people, your personality and sense of humour,” says Eva. While she keeps her website minimal, a quick glance at her Instagram shows a fiercely quick-witted, artistic eye — traits potential clients eagerly look for.

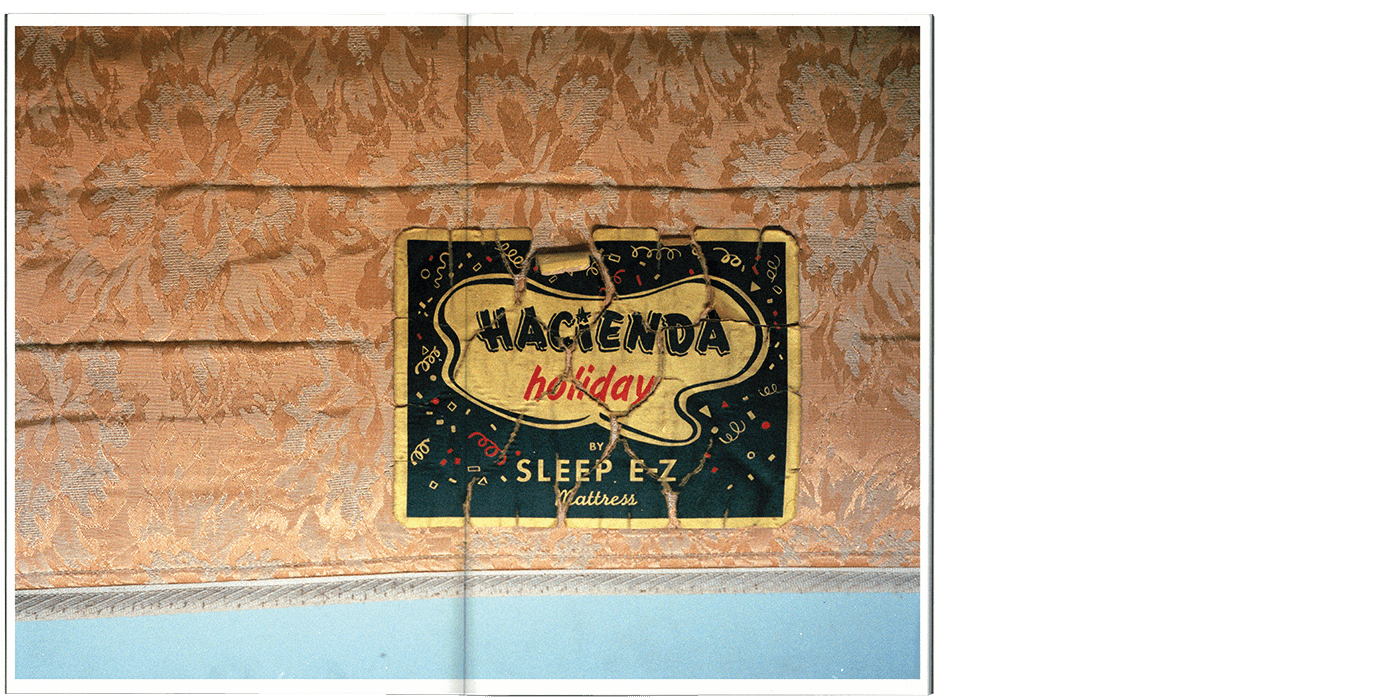

Likewise, Brian keeps his web presence minimal, his current preference is to have “the most simple website known to man.” He finds new work through referrals from past clients and friends, though he has at times blindly emailed people he would like to work with. Whatever the route, Brian has created a design niche for himself, with recent collaborations with Brian Cross (B+), Gangster Doodles and Gilles Peterson, and work perks bringing him as far as Los Angeles, Tokyo and back.

.png)

George believes that attempts to elevate design work with slick personal branding is farcical. “The personality comes before the work and I think it should be the opposite.” Instead, he believes that “good work begets good work” and keeping an open mindset expands horizons, helping to naturally achieve professional goals. George has recently deleted his Instagram calling it “the death of my own personal brand” while admitting it is “one funeral I am happy to attend.”

Does it help to be Irish?

If getting work as a freelancer is influenced by who you are and who you know, is being Irish is a ripe-and-ready source of projects in itself? “New Yorkers love Irish people”, according to Eva, who found that being European gave her an edge when working with fashion-related clients. She uses her seniority to address discrimination in the creative industry and proactively promotes the work of BIPOC (black, Indigenous and people of color) for new hires and collaborations.

The C-word

Freelance designers were not immune to the uncertainty of the pandemic as clients struggled to keep their own businesses afloat. Eva took advantage of some time off work to find a studio space and focus on self-directed projects, contributing to Quarantine Zine and designing to-go packaging for bars Ramona and Elsa during the time. With much of his clients working in the event and music space, Brian was also affected by cancellations, closures and delays, at times working at about 20% his normal capacity. Working remotely at home in Mayo, George used the lockdown months to reflect and detach from his hectic city life in Berlin.

In an industry which places value on social media followers and likes, for Eva, Brian and George, community is more important for bringing in new freelance work. While an Instagram ‘like’ gives a short-lived boost to the ego, often the designers who are busiest are working far from the gaze of social media validation. These freelancers sidestep self-congratulation, opting instead for true connections with the right clients. For them, freelancing is an opportunity to refresh their personal practice and find a new focus. Despite not having the safety blanket of employment during the pandemic, these freelancers are now armed with a self-directed survival kit to keep afloat in the next societal apocalypse.

__

Eva Hogan is a creative director in New York, who mainly works in-house with clients, managing their projects and teams.

Brian O’Tuama is a designer with his own practice working from a shared studio in Hackney, East London.

George Beattie is a designer and art director at Carharrt WIP Berlin. He also works from time-to-time on freelance projects from Berlin, Mayo, or campsites further afield.