As part of the ongoing process of developing content for 100 Past we have made contact with many people who have made a significant contributing to Irish visual communications. Tony O’Hanlon is one of these people.

We asked Tony for a story or insight on the activity of Kilkenny Design Workshop (KDW) during his time there, instead he chose to remember his good friend and colleague Richard Eckersley. Best known for experimental typography designed to complement deconstructionist academic works, Eckersley worked at KDW from 1974—1980. Tony wrote this piece shortly after Richards death in 2006.

…

I have been reminded of Richard this morning. While watching my daughter feed corn to the pigeons alighting on her arm in St. Mark’s Square in Venice, I recall an evocative image developed by Richard for the festival held in London during the 1970s entitled A Sense of Ireland. This image depicted a silhouette of a lone figure moving in the direction of a pigeon, which having been disturbed, has taken flight. Having shared studio space during this period I can clearly remember that the image of a bird had been sourced from a photograph of St. Mark’s Square. Richard had an acute facility for creating images which encapsulated the very essence of what lay at the heart of a design problem. Perhaps that is why this particular image remains very strong with me — I cannot help but equate the lone figure, and his encounter with the bird, with Richard himself. Never complacent, never allowing feathers to settle, always quietly pushing for a more interesting response.

I first met Richard Eckersley in 1973 in the canteen of the London College of Printing when I was as student there. On the day in question the poet Robert Graves had returned from Spain to meet his son (a fellow design student) and was holding court in the college canteen. I was invited to the table by a tutor, Trilokesh Mukherjee, and introduced to Richard, who was visiting his father, Tom Eckersley, who was Head of the Design Department. Our meeting at best could be described as cordial and distant. Six years later we would meet again in Kilkenny Design Workshops, where we would work together for the next six years and become close friends.

So that one can better understand how Richard fits into this story, I think it is necessary to give some background to the environment where he worked and lived in Kilkenny. In 1964, with the help of a group of Scandinavian designers, the Irish Government established a state sponsored design service: Kilkenny Design Workshops. The Government’s intention was to improve the design standards within the country, in order to rejuvenate existing industries towards exporting their products and make new ones more competitive. A period of idealism followed. Design was pure, creative and for a long period unpressured by commercial realities.

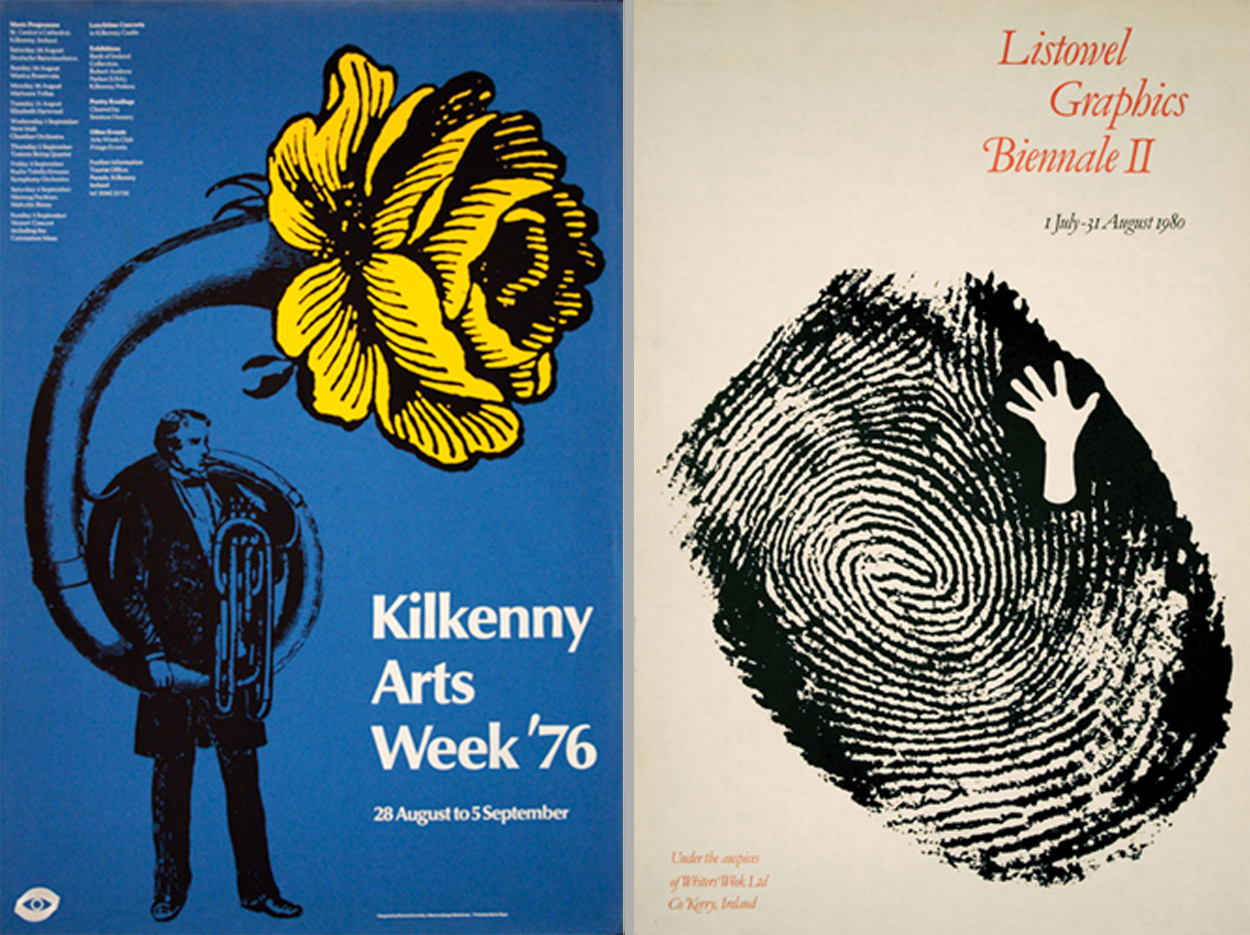

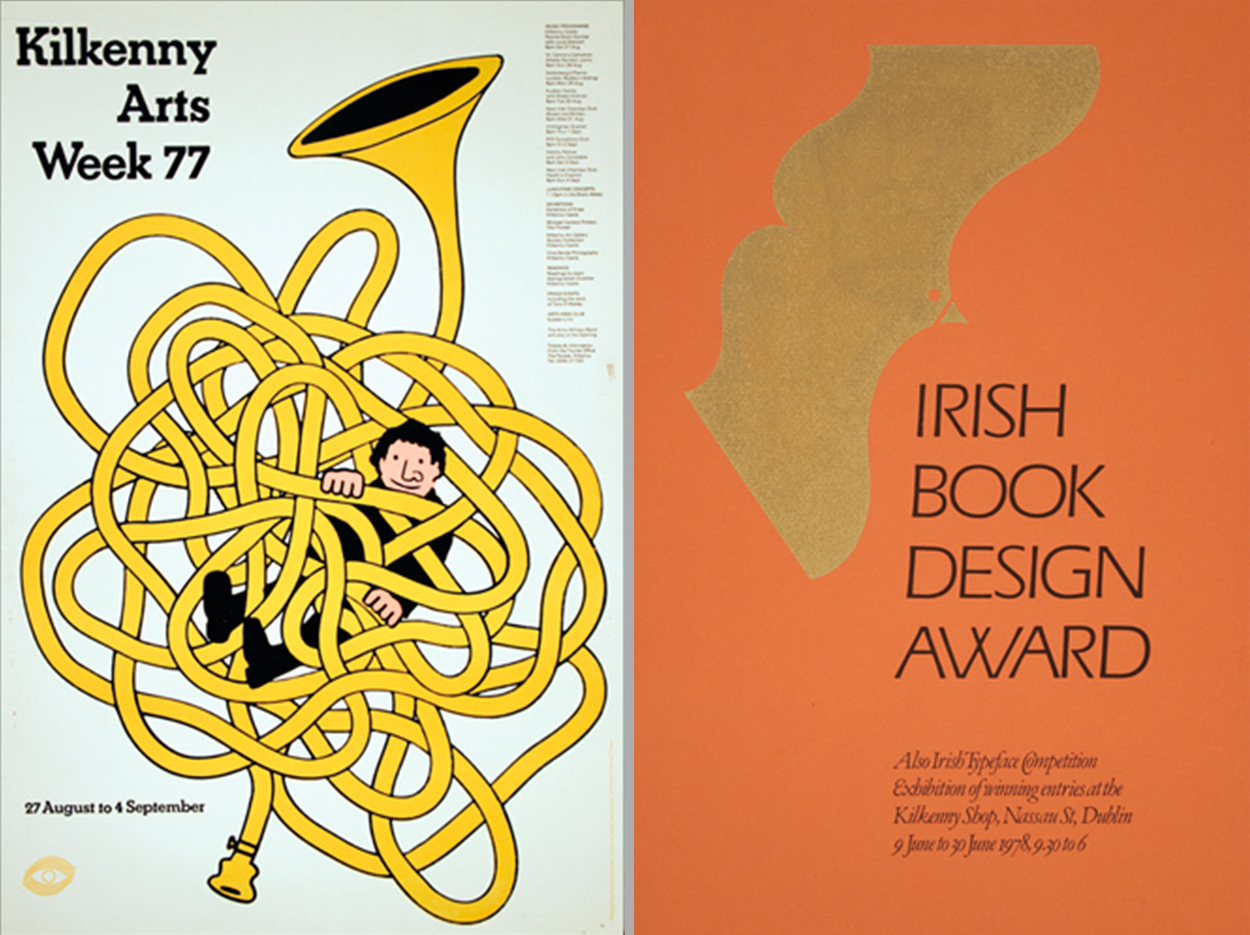

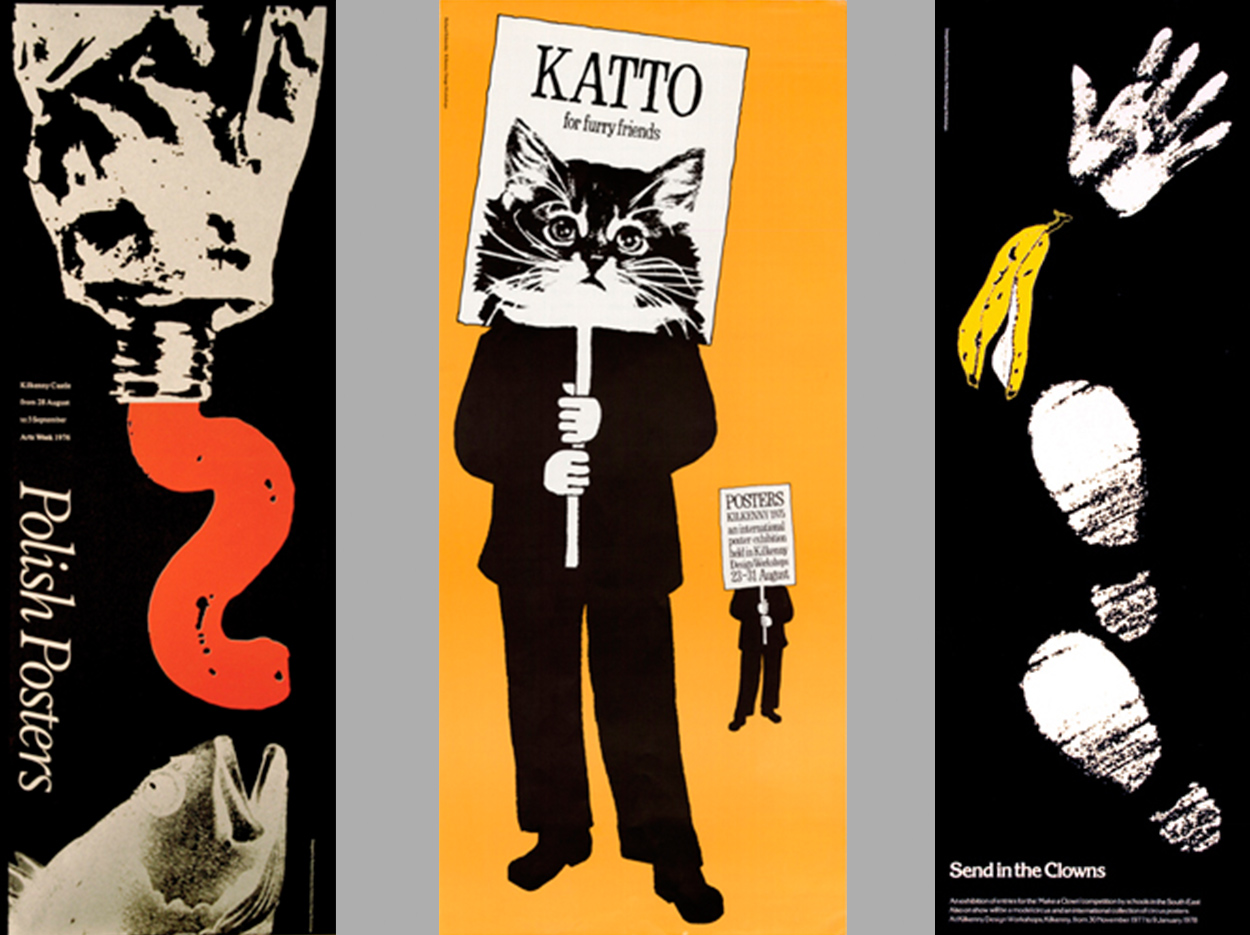

A strong ideas-based philosophy began to take shape, and a definite “Kilkenny” approach became evident. Richard’s influence was central to this. The promotion of design through exhibitions, design events and student competitions during that period made for a unique environment. The most interesting work came from the private sector. With much of Kilkenny’s funding coming from the State the studio was obliged to undertake many projects from the public sector. Some notable work was produced for individual Government departments, but on the whole these were the exception. That the amount of effort invested into these projects never seemed to justify the results proved frustrating to the designers. Bureaucratic fumbling appeared to reduce many interesting projects to a stale compromise. Almost every Government department could have benefited from a competent graphic design service. As it was, the Irish Post Office appeared to be one of the few departments to show an interest in Kilkenny. Richard produced some memorable work for the philatelic section of this department.

Looking back on the work Richard produced at that time, it is difficult to isolate the characteristics that define it. There were no half measures with Richard. I am certain his greatest challenge was to himself, then to the design problem and then finally to the client. His approach was sleuth-like — looking at the problem from every angle imaginable, rejecting the obvious, digging deeper - juxtaposing ideas and images until finally a solution was reached that appeared so seamless - so simple - one would never imagine the effort, the number of cigarettes and long hours spent struggling to arrive at a place where he could finally “let it go”. In short, his approach was an visual expression of his keen intelligence with much of the work giving expression to his verbal wit.

He was unselfish with his time and knowledge and with his assistance to students. He admired the work of Robert Massin, Fletcher, Gill, Derek Birdsail, Brownjohn and Saul Bass. Indeed, through the establishment of both the Irish Book Design Awards and the Kilkenny Design Awards, Richard managed to have at least one or two International judges appointed to the selection jury each year. Non-Irish designers visiting Ireland would more than likely visit Kilkenny Design. Through such visits, designers established relationships with individuals and institutions outside Ireland that survived the closing of Kilkenny Design. These relationships continue to this day.

Richard had ‘blue blood’ design credentials. He could have opted to work anywhere. It was curious that he chose to work in the quiet backwaters of Kilkenny. Perhaps the attraction was the freedom this afforded him. Backwaters that he could cast a fly over. He was an accomplished dry fly trout fisherman. In an effort to introduce me (a mere wet fly man!) to the dry fly technique Richard presented me with a split cane rod designed by the architect that designed the Savoy Cinema in Paris. Together we fished the River Nore, Lough Corrib, and the Function River at Three Castles, where the Eckersley family lived. He stalked individual big fish … and occasionally caught them. The Function river yielded the best of them. Indeed Three Castle House (a rectory built in the late Georgian tradition) became his home for many years. Richard and Dika, his Swedish wife, restored this wonderful house where the Eckersley parties are still remembered. The rooms must still hold the strains of Billie Holiday, Stan Getz and Miles Davis. Long nights, long refectory table, long drinks. Spaghetti, wonderful views of the river and surrounding countryside and wine. Drink played its part in all our lives, which prompted the legendary Dara O’Loughlin to comment on Richard one evening: “There are few in life I would open my door to at four in the morning.”

Richard cut a strange figure in those Kilkenny days, resembling a Marxist revolutionary in his Maoist auberine and tan coloured corduroy suits. It was often remarked that his face bore a strikingly uncanny resemblance to the young Eamon De Valera. He was not easy. You chose your words carefully. In some ways, he was at his best when he was at his worst. He might stimulate a conversation with what might appear an insult; this was usually when the direction of the discussion was not to his liking or he was bored. If the conversation remained in the same vein, his standard reaction was to storm off in disgust only to reappear hours later looking contrite. Yes, he was difficult at times but that was Richard, warts and all. I think we drove each other half mad with the lack of a wider social circle and too tight a working environment.

Richard spent ten years in Kilkenny before taking up a year’s teaching at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. His portfolio he described at the time was “an Irish bouillabaisse, heavy on saffron, light on garlic”. In 1981, Richard made a further move to Lincoln, Nebraska. For the next twenty years he would work designing countless volumes at the University of Nebraska Press. He was also active as a visiting and workshop lecturer. His work has received many accolades in both Europe and America, notably a silver medal at the Leipzig Book Fair and the Carl Herzog Book Design Award. Perhaps the most gratifying was his designation as a Royal Designer for Industry by the royal Society of Arts, an award which in 1963 his father had also received.

Three weeks before Richard’s death I had a telephone call from him. He had difficulty with his breathing. There was an urgency to his conversation. I filled him in as best I could about the recent Kilkenny Design commemorative exhibition, which he could not attend due to ill-health. He spoke of our days in Kilkenny together and ended up stating, “We were making up the rules as we went along.”

He was wrong there. With Eckersley there were no rules.

…

From the book “Remembering Richard”

Richard Eckersley (1941-2006)

as remembered by his friends and colleagues.

Images © www.richardeckersley.net

Tony O’Hanlon

Subsequent to his formal education at the London College of Communication, Tony worked in Kilkenny Design Workshops from 1977-1986. From the late 1980s to 1900s he worked as Principal designer at Digital Equipment International where his work involved mixing traditional design with Information technology. Education activities included external examinership in Belfast College of Art and DIT to running The Digital Design Awards. In 2000 the design partnership Propeller was formed by Tony and Peggy McConnell. Exhibitions of Tony’s work have been mounted in the Paris Mint at the Art of the Poster and at the German Poster Museum. His work has been published in Novum Gebrauchsgrafic, Graphis, Chaumont and Lahti Biennales. He has been designing his website for the last 15 years....or more.