With 39% of all work submitted to the 100 Archive being made for the cultural sector (more than any other category), it is clear that design plays a notable role in how we express our culture. Crossing over between largely cultural and International projects is the question of how Ireland is endorsed and represented abroad. In particular, how do government funded initiatives go about promoting Irish culture and enterprise on an international stage?

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade explains that ‘Ireland’s culture is a unique national strength, which defines us on the world stage. The global impact of Irish culture is one of our greatest competitive advantages, acting as a ‘door opener’ that helps to secure jobs, trade, investment and tourism. It’s also our most effective way of connecting with the global Irish diaspora and the cultural sector is a dynamic and growing part of our economy.’ (1)

Much of Ireland’s culture, as manifested in the Archive, is discussed over in our Building Culture section and of course, many of the cultural festivals and events hosted in Ireland cater to national and International audiences. This article, however, is concerned with how Irish culture is demonstrated beyond these shores, through designations, World Expos and other means.

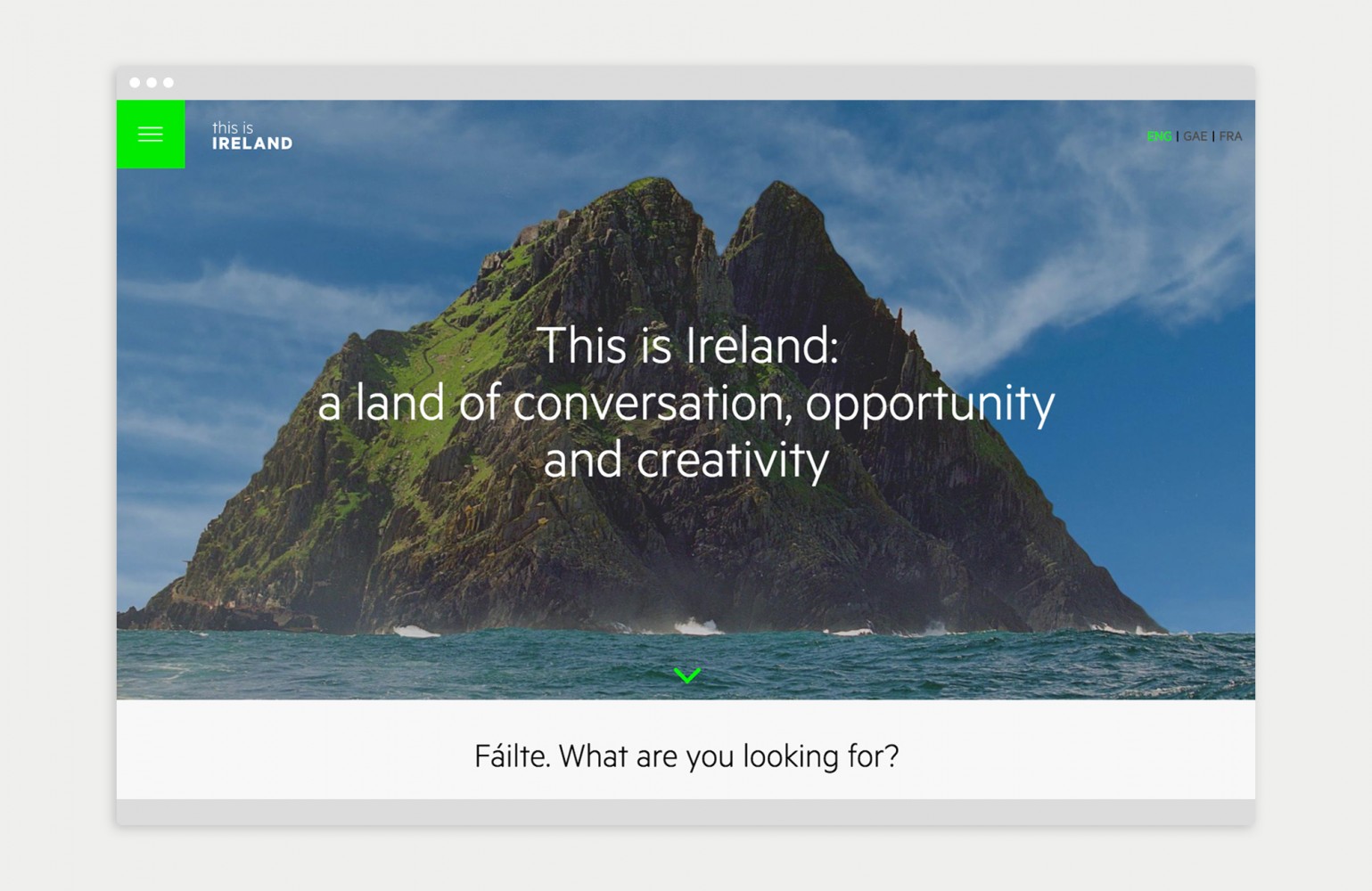

It’s fitting then that the title of this article, whilst referencing the well known Padraig Pearse poem and 1959 George Morrison documentary film also references a project submitted by Zero G on behalf of Map Irish Design funders Clár Éire Ildánach (Creative Ireland Programme). This is Ireland (ireland.ie) created a positioning for Ireland that transcended individual sectoral concerns, presenting a myriad of individual stories from Ireland that together communicated a country that recognised the value of creativity, culture and community. The designers state that ‘The launch of the site proved to be a successful example of cross-departmental government communications and laid the foundations of acceptance in government of the benefits of a more coordinated approach to national identity.’

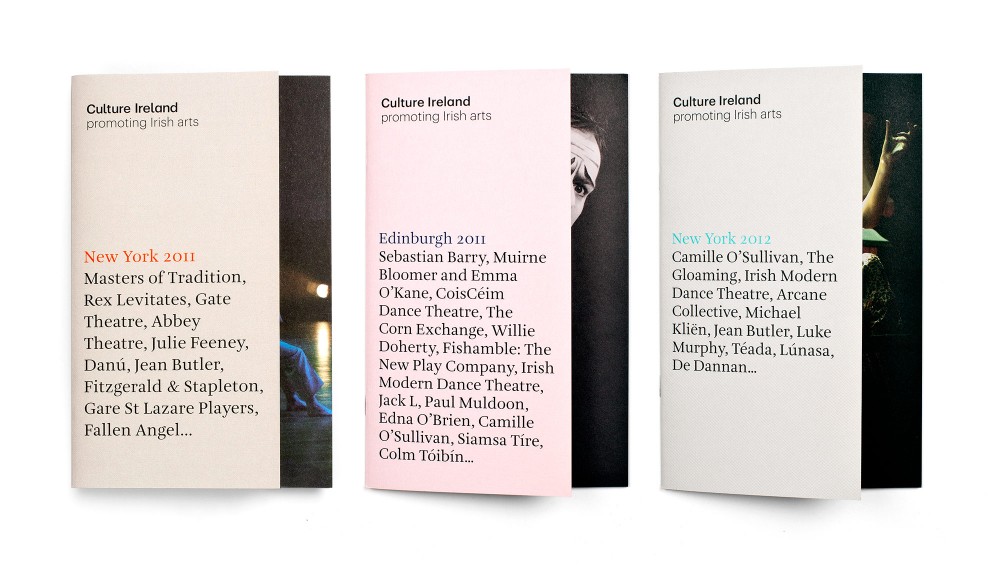

Whilst ‘The role of public engagement and expression during the centenary of 1916 demonstrated the societal value of culture and creativity’ as attested to in the establishment of the Creative Ireland Programme, 2016 was far from the beginning of official Irish cultural representation abroad. Indeed, it’s worth noting that discussions on the establishment of an Irish Arts Council coincided, at times unfavourably, with those of the Cultural Relations Committee, as Brian P Kennedy states, ‘it was that while rejecting the establishment of a Council of Culture or Arts Council to promote the arts within Ireland, the Government agreed to set up an Advisory Committee on Cultural Relations to promote Irish culture abroad.’ (2) Indeed Culture Ireland, submitted by Aad, specifically operates a range of funding programmes to support and promote the presentation of Irish arts internationally.

We can see through the 100 Archive that the Science Gallery, founded in 2008 became a founder and part of the Global Science Gallery Network pioneered by Trinity College Dublin and thereby hugely significant as an Internationally relevant Cultural organisation.

The Irish Film Board, now Screen Ireland, has operated with the exception of a 1987-1993 sojourn, since 1981, but the economic potential of film to Ireland has been long recognised. The 1927 UK Cinematographic Act required that companies exhibiting films in the UK reserve 10 percent of screen time for domestic productions, ‘effectively blockading funds in the UK,' and defined any part of the Commonwealth, including Ireland, as British. This meant that Ireland could benefit from these funds and coincided with a time when Sean Lemass ‘had turned his thoughts to ways in which overseas production might be attracted to the country’ (3). Screen Ireland now boast Ireland’s competitive tax incentives, an excellent skilled crew base and a well-established studio and technical infrastructure, much of which is discussed in its production catalogues, hosted on the archive on behalf of multiple studios in 2010, 2013, 2015, 2016 and 2017. Screen Ireland's mission is to support and promote Irish film, television and animation through fostering Irish artistic vision and our diverse creative and production talent, growing audiences, and attracting filmmakers and investment into the country. Irish television on the International stage is also represented in the archive via the 2015 in-house RTÉ Player International.

Relatively early on in the archive and discussed separately within Map Irish Design here, was PIVOT Dublin. Premised in demonstrating the value of Dublin’s design significance and output it also had the inverse effect of greatly adding to that output and did so through a range of studios, groups and events. PIVOT was borne out of an application from Dublin City Council, spearheaded by City Architect, Ali Grehan, to be designated World Design Capital in 2014, a city promotion project established to celebrate the aims and accomplishments of cities using design as a tool to reinvent themselves socially, culturally and economically. It was perhaps displayed best in an international context through its bid book by Red & Grey and Shape film (Johnny Kelly) and accompanying website (Aad).

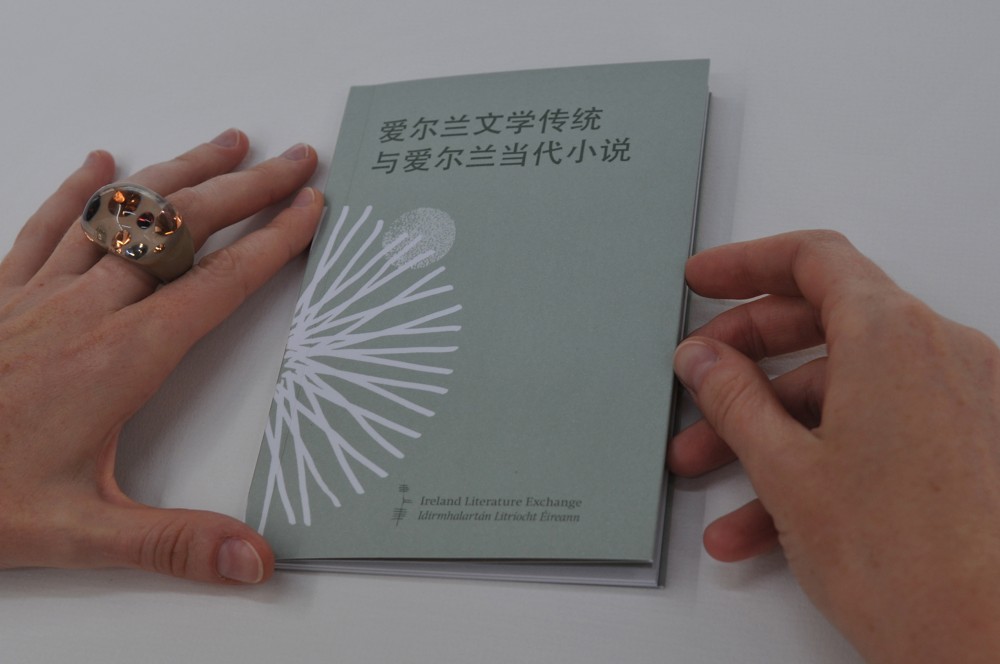

In the PIVOT Dublin bid book, Linda King discusses how ‘the alliance of culture, design and technology … defined Ireland’s presence at the World Expos of 2000 in Hanover and 2010 in Shanghai’. The former is outside of the 100 timeframe but the latter is represented by Language’s ‘The Irish Literary Tradition & The Contemporary Irish Novel’.

It’s Ireland’s presence at Venice that features most significantly within the 100 Archive. Making Ireland Modern (New Graphic) was originally conceived as the Irish pavilion for Venice 2014 (called 'Infra Éireann’) and was expanded to become a key strand of the Arts Councils programme ART:2016. Making Ireland Modern describes architecture’s role in transforming the physical and cultural identity of the new state through its intercession in the everyday lives of its population.

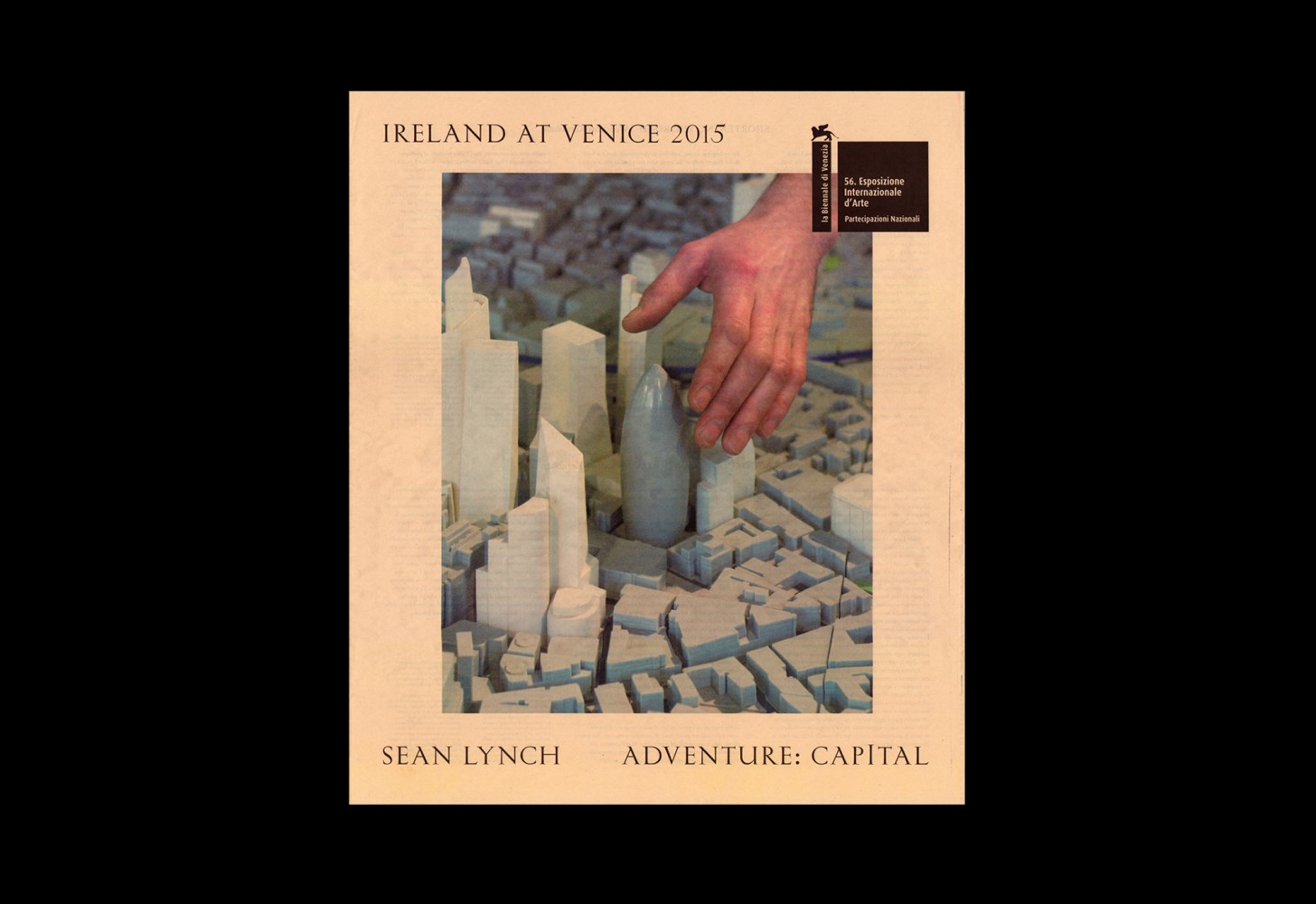

Wayne Daly’s visual identity and collateral material for Sean Lynch’s Adventure: Capital, the Irish pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale. When Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton Architects were selected as curators of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition (La Biennale di Venezia) not only was it a significant International endorsement of Ireland’s cultural and creative output but it allowed Irish Graphic Design an impressive platform. Atelier David Smith’s response, in the form of its identity, catalogue and supergraphics and exhibition sought to visualise and communicate the ‘generosity of spirit’ and universal ideals at the core of the curator’s FREESPACE manifesto. The Free Market exhibition identity submitted by Detail. Design Studio, the Irish pavilion at the Biennale Architettura 2018 highlights the generosity, humanity and possibility in the common spaces of Ireland’s market towns.

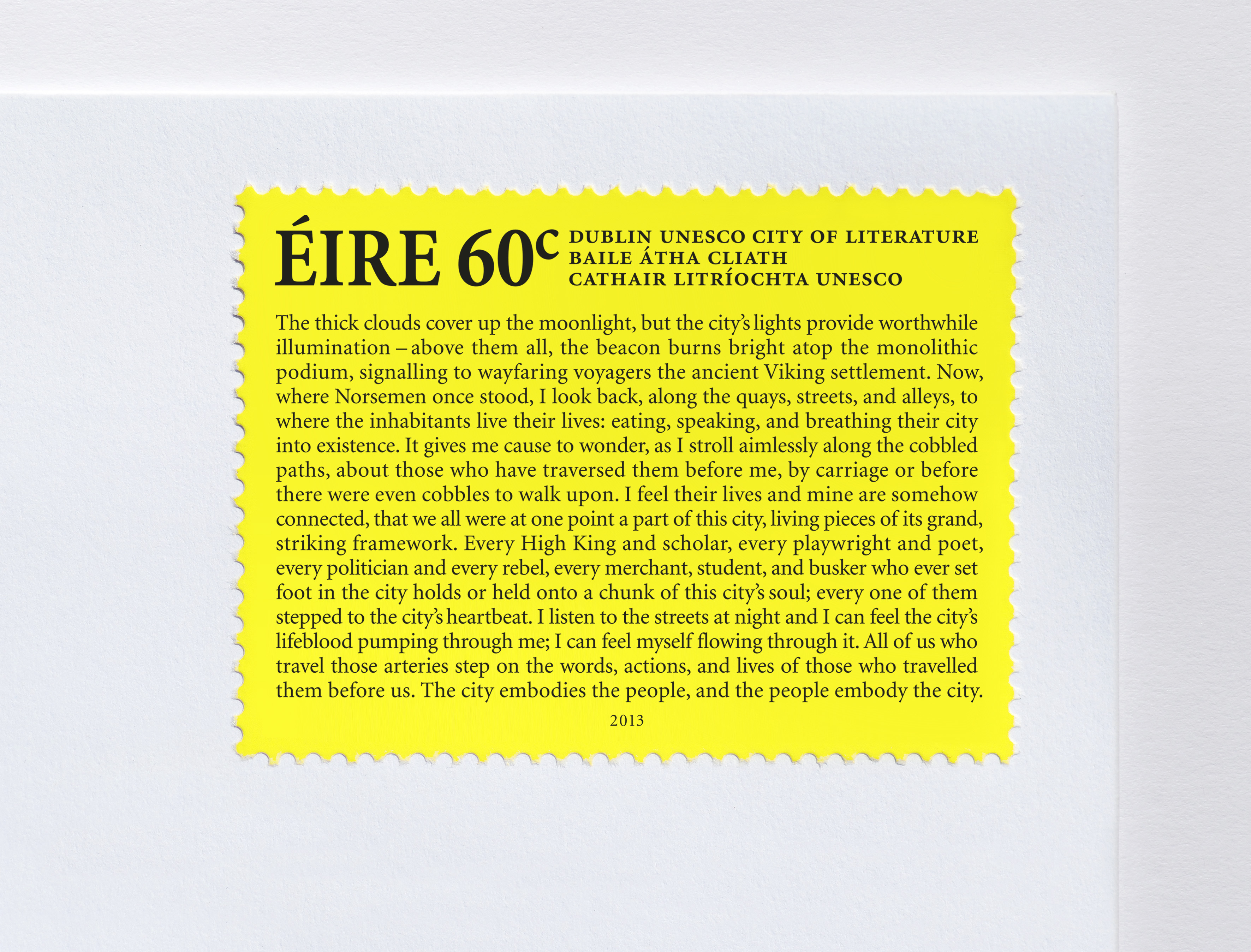

Culture as connector is championed too by Aad on behalf of Ireland’s presidency of the EU in 2013, revealing connections between language, colour and artworks. The community and public aspect of design and culture is illustrated perfectly by The Stone Twins Dublin UNESCO City of Literature Stamp which instigated a competition, in collaboration with Roddy Doyle's ‘Fighting Words’ creative writing centre, that invited young people to write a story. The winning entry by teenager Eoin Moore is reproduced on bright fluorescent yellow. The sense of community and ‘ground up’ involvement is exemplified too by Unthink’s Galway 2020 Bid Book for European Capital of Culture designation. As we now know, the designation was achieved but is now undergoing an enforced contraction of its programme.

The Design and Crafts Council of Ireland (DCCoI), discussed alongside PIVOT Dublin here, is represented significantly within the archive with work submitted by some of Ireland’s most respected studios. The Vernacular and Weathering exhibitions took place at the London Design Festival in 2013 and 214 respectively. Irish Design 2015 (ID2015), led by the DCCoI was part of the Irish Government’s Action Plan for Jobs. Through a year-long programme, culminating in over 600 events, it worked towards raising the profile of Irish design, with Liminal, NY Now and the ID2015 Travelling Exhibition all showcasing Ireland’s design strengths and representing Ireland on an International stage. The following year, the Global Irish Design Challenge Exhibition, submitted by Unthink, showcased Irish designers changing the world. It feels like the perfect project to wrap up with - the idea for the project grew from a desire to seek out designers and innovators who are driven to find solutions to the challenges humanity faces. Curator Louise Allen explains ‘It creates a platform for game-changing Irish design innovation, while activating and connecting a broad global network of Irish design talent.' (4) We need these kind of solutions now, more than ever.

(2) (1995) Dreams and Responsibilities: The State and the Arts in Independent Ireland, Brian P Kennedy

(3) (2009) ‘Projecting or Protecting Ireland? The Department of External Affairs and Hollywood 1946-1960’ FLYNN, RODDY. In: BARTON, RUTH, Screening Irish-America: Representing Irish-America in Film and Television, Dublin, Portland: Irish Academic Press

(4) http://globalirish.irishdesign2015.ie/

____

This article is part of a research project called Map Irish Design, undertaken by the 100 Archive and funded by the Creative Ireland Programme. The project explores how design affects life, culture, business and society in Ireland, as viewed through the communication design work gathered by the 100 Archive since 2010. See the project at map.100archive.com