Walking around Dublin today, with its countless clothes shops filled with specially selected pieces, it is almost impossible to imagine (or remember, as the case may be) that 25 years ago, the fashion retail landscape of the city was very different. When buying clothes then,the choice was either the affordable and mundane or the expensive and exciting. Rarely did the Dublin shopper encounter the combination of affordable, exciting fashion that made a statement.

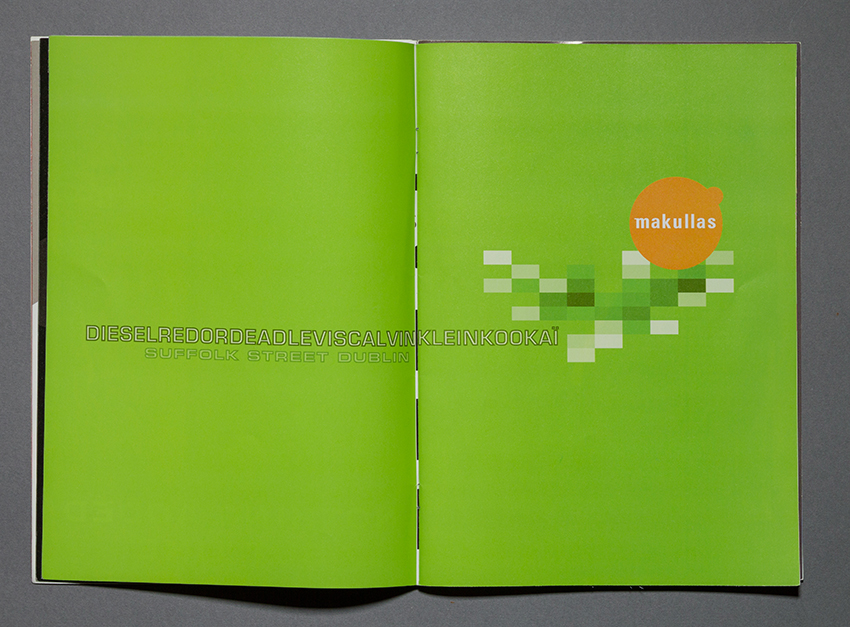

Then along came Makullas on Suffolk Street. Taking its name from the previous occupant, music store McCullough Piggott's, it was a shop that scribbled all over the retail rulebook in Dublin, which many shops since then (unwittingly or not) have taken their cues from. Bringing together a mix of fashion, music, art and graphic design, it reflected the club culture of the time. It was a maverick, a pioneer: an independent retailer, bringing affordable fashion and design in a space that was social, experimental, fun and, as many of us can attest to, very memorable.

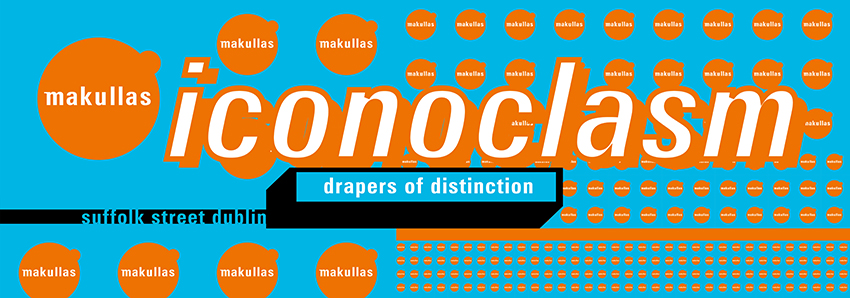

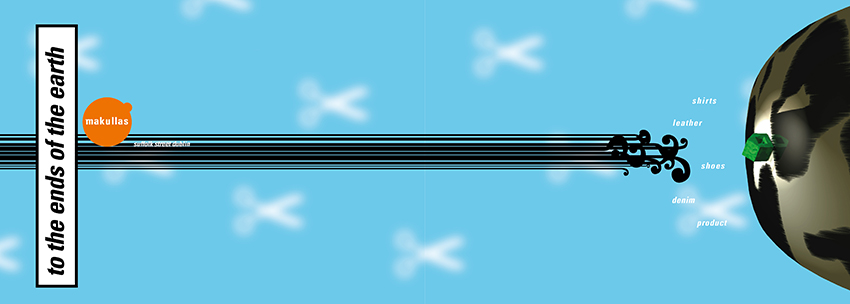

A key part to all this was the work of graphic designer Niall Sweeney. He was, he says, inspired by a trip to Tokyo, to “meld that scintillating Japanese excitement with something somehow 'Irish' and create something new”. The design approach, as a result, was less about the clothes and more about the social and cultural zeitgeist. It wanted to make people feel, rather than tell them how to look or to what buy. Visually, the graphic design merged a vibrant use of colour and humour that pulled no punches, wore its heart on its sleeve and took its audience seriously.

I asked Niall about his take on that exciting time.

Before Makullas, what were you doing (design-wise) up to that point?

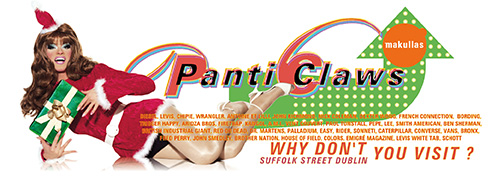

I went to Dun Laoghaire College of Art and Design (DLCAD) from 1985-89, now IADT. The college was pretty small at that time, and I think this positively encouraged a multi-disciplinary approach to work that has pretty much been my way of working ever since. I guess a 'moment' would have been when I started going to nightclubs, particularly Sides Danceclub in 1986, for which I started doing flyers and installations, working with Frank Stanley (who would later became co-founder and creative director of Makullas). Dublin in the late 1980s (and through the 1990s) was a key period to have grown up in. Ireland was, as usual, bobbing around in recession, and there was a strong DIY creative ethic with all my friends, who run the gamut of artists, photographers, performers and drag queens. We realised that if we didn't build our own stage to dance upon, no one else was going to do it for us, so there was a lot of experimenting in nightclubbing-fashion-performance-art-technology-music going on and it was a time of great social and political change.

I was doing (more or less) commercial work throughout college and then set up a loose studio with friends, which lasted, in various guises, until I left for London in 1998. Throughout this time, it had always been a collective collaboration with friends that had driven the projects – whether 'design' in the strict sense, or the broader more performative, social, political, theatrical senses, which usually end up in music and dance at some stage in the evening.

Ironically, though the first Apple Macs only arrived in DLCAD as I was leaving, I was brought in as design director of a burgeoning interactive media research group in Trinity College in 1992 (which would then go on to become X Communications). It was set up and directed by the fantastic Marie Redmond. So I was running between the design studio in Temple Bar and the research lab in Trinity — with very blurred boundaries around their increasingly overlapping projects. The multi-disciplinary approach to work went into overdrive.

How did your involvement in Makullas come about?

Makullas emerged out of a long working relationship between Gordon Campbell, Tony Forte and Frank Stanley. It was as if it had been waiting to happen and this was the moment. So many things and people and events came into alignment. It was 1993 (or was it 1994…?) when it opened. Dublin had hit its groove and we were doing clubs, making music, designing magazines, installing art, creating riots - generally doing lots of stuff and, in some cases, changing the world - our world. And it seemed like all my friends were involved in almost all of everything, which made the momentum and impact much greater (and much more fun). Makullas was big, very big, especially for an independent Irish retailer. It had an international outlook with Irish nous, and embedded itself in the new wave and generation of the time. It was the DIY ethic on a mammoth scale. No one else was going to do it - and do it that way.

The design and advertising strategy were fairly radical for the time, was it a case of great work is evidence of great clients (who let designers get on with the work)?

I think that is right. That, plus youthful endeavour, arrogance and a desire to look to the world around and embrace it. In the end, the design work still had to sell jeans and jackets and t-shirts (and Emigré Magazine, which we sold alongside the shoes!). But there was a greater picture, something that was reaching out to make a statement. Ireland had a tendency to go abroad, come back and do exact rip-offs of things seen elsewhere, rather than absorbing influence and then creating something new, something that shouts with its own accentuated voice and language. No compromises. No nostalgia. No surrender (!!!). There was a lot of unfettered innocence.

The 'strategy' extended way beyond the magazine ads, posters, DART banners and bus sides that proclaimed 'LOVE' years before that word hit Dublin billboards. There were DJs on a Saturday afternoon, playing as loud as the Friday night before (and mostly to the same crowd, who were all probably still up, now shopping while dancing). Makullas was a generous and determined supporter and promoter of all kinds of art and music events and embraced all and any kind of poly-sexual beings and lifestyles. The table full of flyers (when flyers were really something to collect) that proudly sat halfway up the giant steel and glass staircase heaved under the weight of opportunities for the weekend ahead. Makullas looked to the now and to the future. That and the price of silver knickers and Levi 501s.

What were your reference points/inspiration/influences for the project?

The Celts and the Japanese go out for a quiet drink on a Thursday and come back four days later, having had 'le weekender'. And of course, there was the worldly excitement of new technological developments impacting on design and culture in so many ways. We were being influenced left, right and centre and were just in free fall through it all. Some of [the work] was great; some not so much (some probably far too influenced, especially in light of my ranting in the above question!) but that's just as cool. It was all about the doing and never looking back. The work generated itself and its next iteration. Loads of fuck-ups and uneducated guesses along the way! But also, loads of (major and minor) triumphs. And though much of the work was ephemeral, as a body of work, it is still one of my favourite things. Though that probably IS nostalgia talking!

Humour (in its many guises) seems to be an important part of your work – true?

The graphics were all great fun, serious fun. Sometimes they pulled the rug from under the high-brow to build a throne for the low, and sometimes vice-versa. Humour conflates facts and fictions; compacts histories; triggers numinous objects in the mind's eye. There is humour in everything. I am a firm believer in the social and political power of dressing up and having fun — which is what much of design is, really.

You moved to London in the late nineties. Do you feel like an Irish designer or a designer who happens to be Irish? Or does that matter anymore?

Oh jaysus, that doesn't matter anymore. You could just as easily ask am I a gay designer or a male designer or a white designer or an English designer. But, of course, all of my life to date has a direct impact on everything I do — so the Irish part is a key and significant factor and one that I love and engage with. Sure, I never really left – 50% of the work we do in the studio is still based in Ireland or of Irish origin. It's all in the specific mix. This reminds me of one of my favourite lines — from the closing scenes of Prick Up Your Ears, where Joe Orton's sister is mixing her brother's ashes with those of his lover (and murderer), Kenneth Halliwell, and she gets mixed up as to how many spoons of each she has put into the urn and Peggy Ramsay quips, "It's a gesture, dear, not a recipe."