It’s fairly common practice for design graduates to leave Irish shores and gain experience abroad, only to return home a few years later to benefit the industry here. Some, however, decide to stay and make their career in their adopted country. One such example is Kevin Finn, who for nearly 20 years has built a successful career as a designer and writer in New Zealand and Australia. Here, he talks about moving to the other side of the world, going out on his own and discusses how side projects like Open Manifesto and DESIGNerd are driven by his passion for design. Words: Eamon Spelman

I don’t recall being overly ‘creative’ as a child - at least nothing more than might be usual at that age. I loved books, 2000AD comics and graphic novels. I tried to draw some of the characters, with mixed success. One thing that stands out was a phrase people often used, usually in negative terms: ‘Kevin, you think too much!’ For years, I never knew how to respond to this. But then — of course — I thought about it, and my response became: “But there’s a lot to think about.” Incidentally, this attitude has helped shape my career as a designer.

Like most designers, music was a huge influence, the 4AD record label in particular. I began listening to Dead Can Dance, Cocteau Twins and This Mortal Coil when I was around 14 years old. The music and the record sleeves had a profound impact and when I finally understood that it was someone’s job to do the ‘artwork’ for the record sleeves, I was amazed. This led me to Vaughan Oliver’s work, who had a huge impact on my formative years as a young designer. As I began to understand graphic design more, Neville Brody’s experimental approach to design was also an influencing factor.

I came to design by accident, stumbling into a graphic design course in Letterkenny (LYIT). However, it wasn’t until my second year there that I knew what graphic design was. I just knew I liked it. It was both exhilarating and terrifying. I was always afraid I couldn’t come up with an original idea and regularly felt like a fraud. LYIT was an incredible place to learn about graphic design, partly because we were so removed from everything and our influences were largely each other, but also because it was a very hands-on course, very focused on the practical side of design. After LYIT, I did a one-year degree in Limerick School of Art & Design, where I was introduced to a more conceptual way of thinking and the course was very self-directed. This had another profound affect on my approach and thinking.

After working in Dublin for three years I moved to New Zealand, which was a huge adventure. It was 1997, I knew no-one and didn’t have a job set up before I got there. What I found there was a very positive attitude and a sense of innovation — one of risk-taking. It took me a while to understand why until I realised that a relatively small country had no other choice but to be anything other than innovative and open-minded. People there were interested in ideas and trying those ideas out. And they were interested in helping others to achieve their ideas. I found this refreshing because, at the time, (outside of working with Steve Averill for 18 months) the attitude in Ireland was less positive, more conservative and also lacked a sense of support for one another. It was the opposite side of the world to Ireland with opposite types of attitude but there were so many similarities: a common sense of humour; the importance of family; an appreciation for the land/nature and a sense of being in the shadow of a neighbouring country (Ireland/UK and New Zealand/Australia). But New Zealand approached things very differently to how they were being approached in Ireland at the time, at least in my experience, and I learned a lot from that.

I always believed getting the job at Saatchi Design was probably the easiest part because the hard part was living up to having the job — every day. I was Joint Creative Director at Saatchi Design Australia for seven years and every day I felt privileged to have that opportunity. When I joined, there were four of us but we were attached to the Saatchi & Saatchi Sydney agency, which had between 140 and 180 people at any one time. I had never been interested in advertising but I learned so much from being part of the agency and from the strategy team and the planners, in particular, about the power of ideas and importance of strategy.

One project that stands out was a promotional brochure called Precision for Spicers Paper. From start to finish, with my co-creative director Julian Melhuish, we invested in the idea and the craft of execution by doing all of the props by hand. We absorbed time and money, worked with an amazing photographer, Ingvar Kenne, and loved every moment of it. And we felt privileged and encouraged when it won a D&AD Yellow Pencil. The reason I love the project is that we had so much fun and there was so much commitment to create something we believed in.

I have always taken risks and this has become part of my experience as a designer. After Saatchi Design, I knew I needed to do something radical. The universe provided when my girlfriend (now wife) took a job in Kununurra, a remote town in the north of Western Australia. I moved from Sydney and an agency of 180 people to a town of 6,000 in the middle of nowhere and being on my own in the back of a house. I moved from a bustling city to a place where the nearest urban hub is a one-hour flight. I had no idea how to set up my studio there, if it would work or if I could pull it off. I told my girlfriend I’d be prepared to stay for one year but we ended up staying for three. It was amazing and challenging. I was once asked if living in remote Australia, away from everything, had made me a better or worse designer — my response was immediate: “Whether it has made me better or worse is for others to decide. But perhaps it has made me more interesting.”

In 2003, it struck me that, like most design studios/agencies, after a while the process became: we get a project, we do the best work we can, we hope to win an award, we get a project, we do the best work we can, we hope to win an award, we get… I could see a treadmill ahead and it scared me. I was scared I’d get bored. I had achieved far more than I ever thought I would but I also knew I had to get out. I couldn’t improve on things if I just continued the same way. So I started thinking about other career paths but none really grabbed me. I considered another option I had set out for myself; rather than get out of the industry, I would go to the heart of it — and question it. Question what I do. Question how we do it and what affect it has. That’s when I decided to do Open Manifesto.

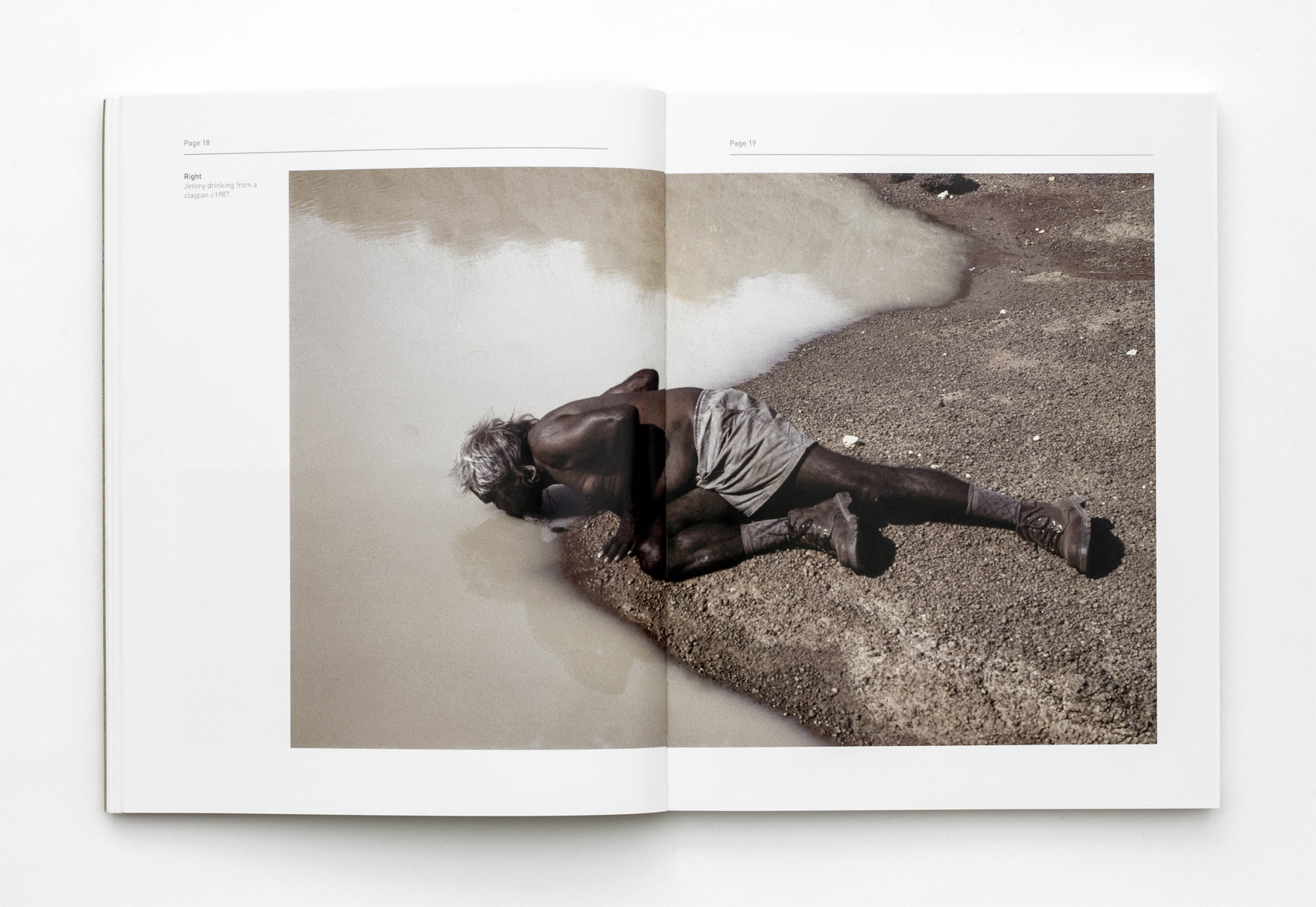

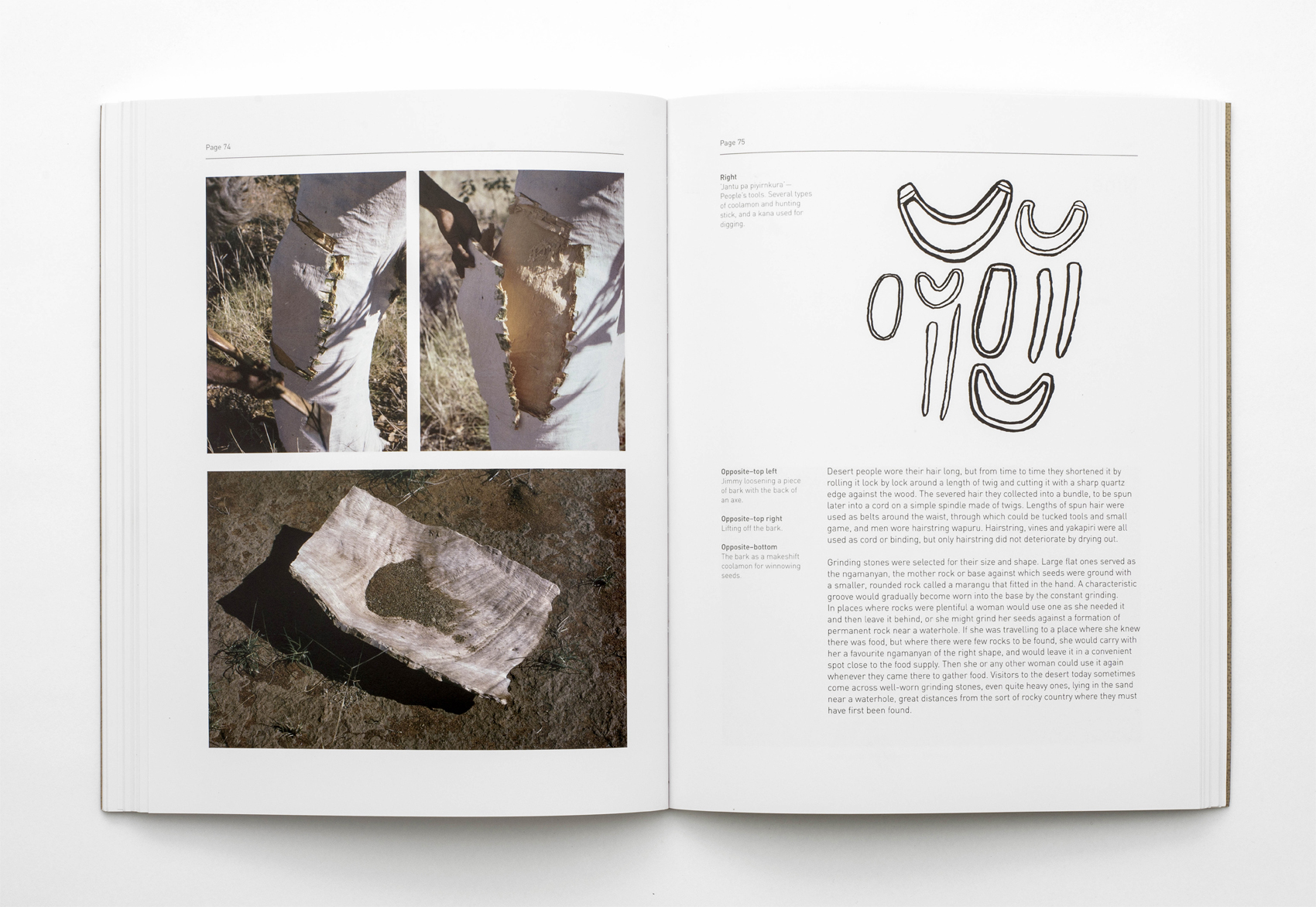

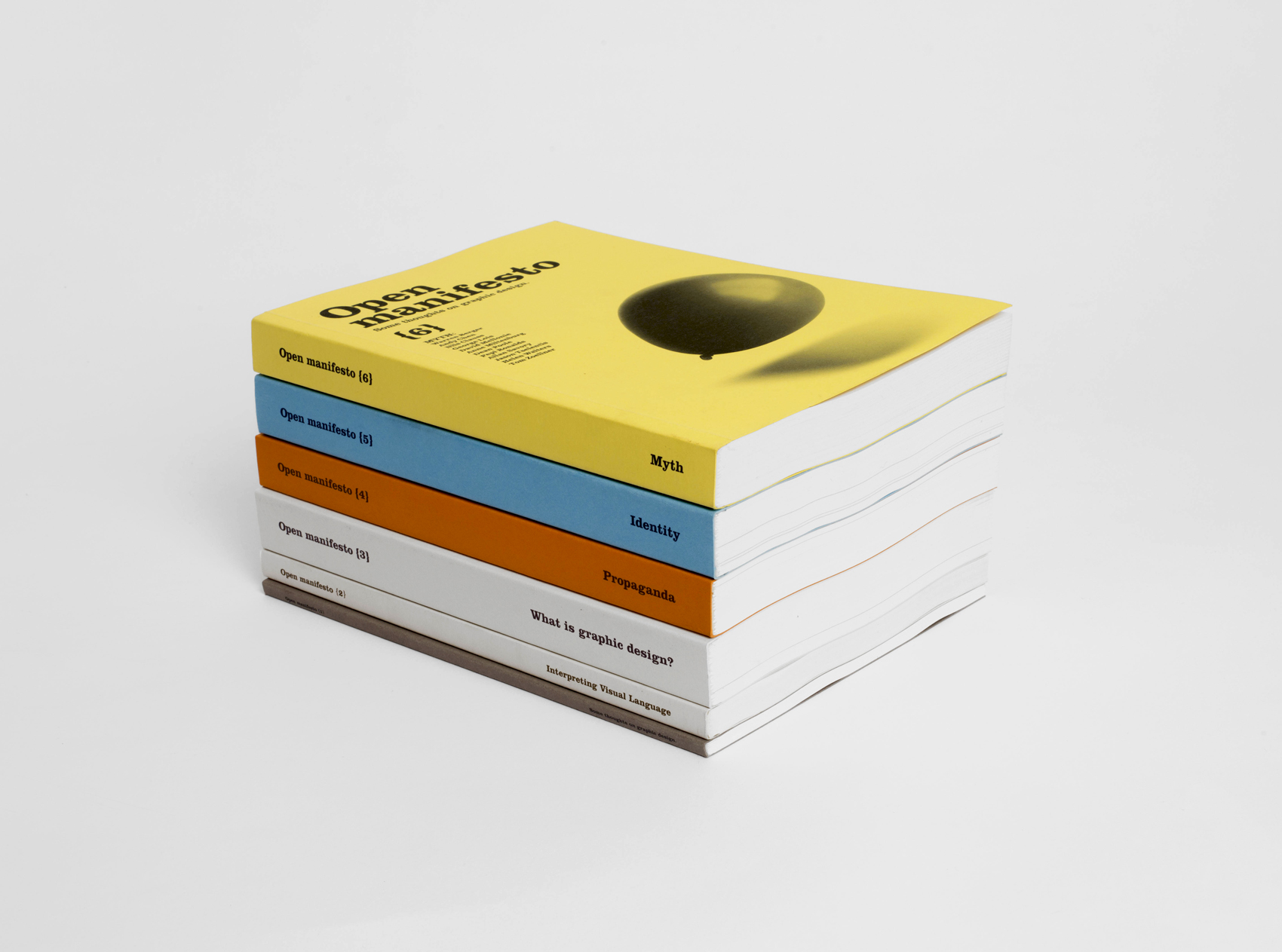

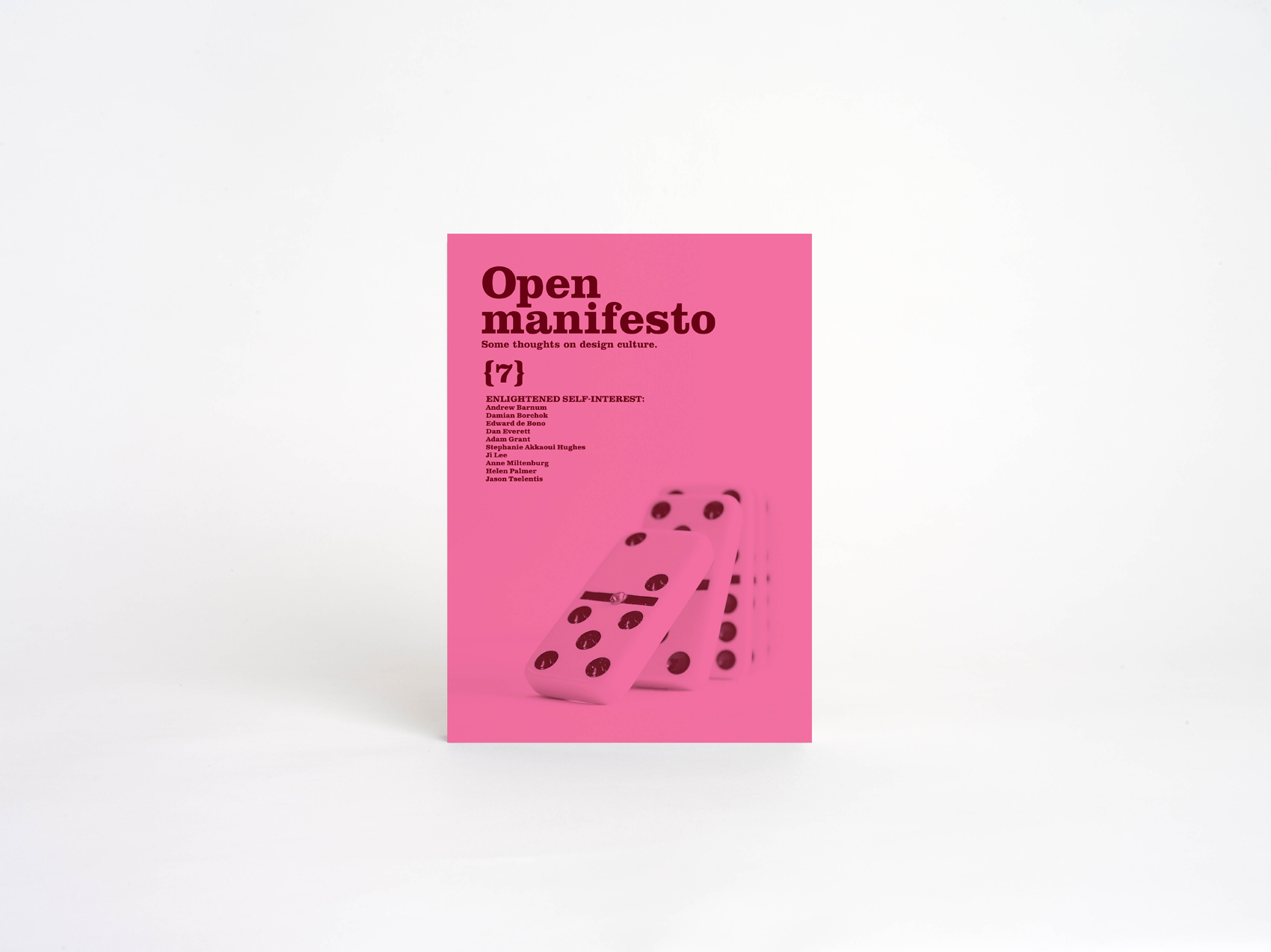

Even though I had been thinking of starting Open Manifesto since I graduated in 1994, I had convinced myself that I wasn’t qualified to publish a journal. I wasn’t an editor, or a journalist. I didn’t know how to interview people or develop content that others might find interesting. I had to overcome this self-created hurdle and just do it. I looked at areas that weren’t getting any attention in our field, areas that interested me. I spoke with a young Aboriginal designer (I had never read anything about contemporary Aboriginal graphic design in mainstream design media), as well as a young Muslim designer (again, I had never read anything about this in the design press). For issue #1 I also did my first ever interview—with Vince Frost. I was terrified. When the first issue was published, I decided to try another. The second person I ever interviewed was Stefan Sagmeister. I was still terrified. From there, with subsequent issues, I have been fortunate to be in a position to mix designers (Paula Scher, Milton Glaser, Bob Gill, Peter Saville, Ji Lee, George Lois, Jessica Walsh, etc) with international thought leaders (Edward de Bono, Noam Chomsky, Alain de Botton, Errol Morris, Adam Grant, etc) alongside an ex-CIA agent, a real-life super hero and a real-life cyborg, among others. Each issue is between 250 and 300 pages. I’m currently working on issue #8. Open Manifesto has always been a way to learn about my field but from multiple perspectives.

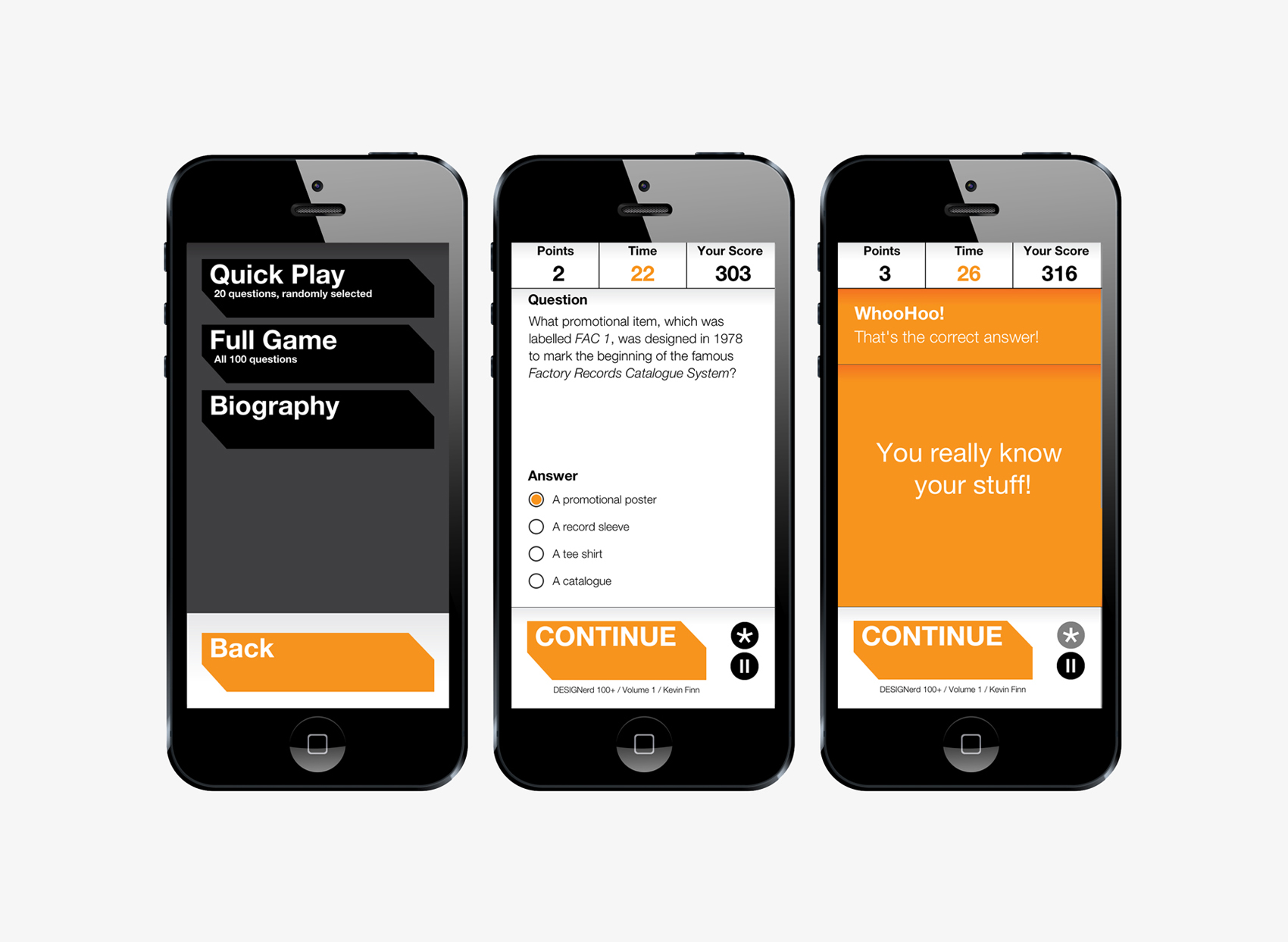

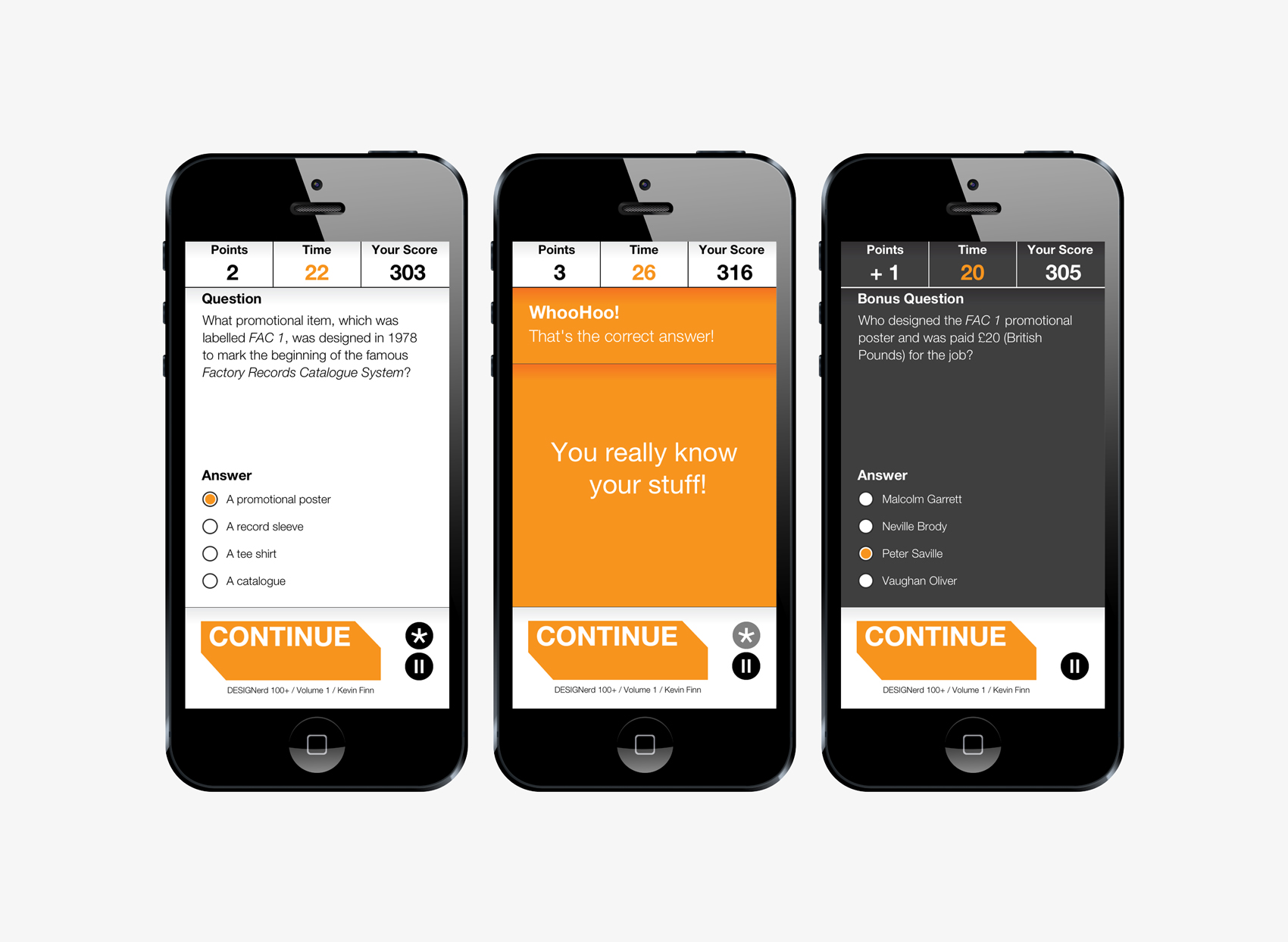

I knew Open Manifesto would be an investment, but an investment in my knowledge. This has been important to me and reflects one of my personal philosophies: There is wisdom in learning. DESIGNerd is similar. Personal trivia questions about graphic design from some of the most respected designers is purely about learning — but in a fun way. Both projects have learning at their heart and, like other designers, learning is central to my approach to design.

Side projects should be driven by passion, not by a resentment for your day job. I think if we consider them as traditional creative side projects, some people tend to do them because their day jobs aren’t creative enough. This is something I fought while at Saatchi Design, where my colleagues were keen to do side projects, which would counter the corporate work we were doing during the day. Side projects are a great way to promote your thinking and creativity. Ji Lee (Creative Lead at Facebook) is a great example of this. But for me, I want my day job to be challenging and as creative as possible. I don’t want to make up for it in the evenings and on weekends with self-initiated ‘creative projects’. That has led my side projects to be more about learning and educating myself (and sharing this with as many people as possible). So for me, side projects — in that way — are about learning and are very important to me as a person and as a designer.

As designers we can be anywhere in the world, whether that’s a major international city or a remote town. That being said, I always refer to myself as being Irish, no matter where I am and regardless of the fact I’ve lived overseas since 1997. Where we come from is important. It is part of our identity. It is the foundation for who we are... And I’m Irish.