Most design agencies are formed through a college friendship or working relationship but, for Charlie O’Neill and Jole Bortoli, it was encountering each other's posters on the streets of Dublin that gave them the idea to join forces and form Graphiconies (later to become Public Communications Centre, or PCC). Here, Jole and Charlie talk to Eamon Spelman about the agency renowned for its arts and cultural work, and the change of direction that reshaped the business, refocusing it on social and political issues.

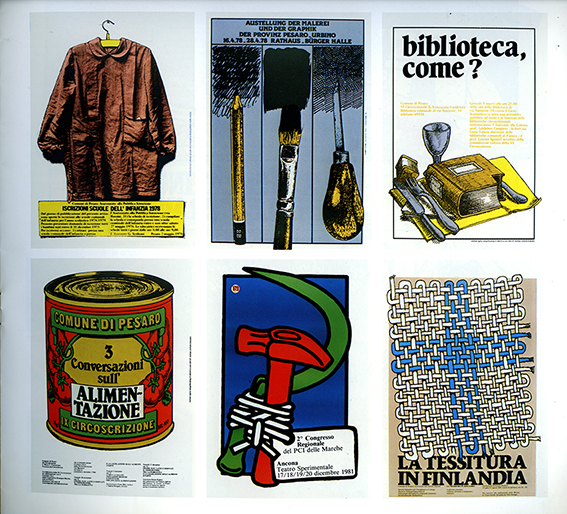

Jole came to Ireland in 1984 from Italy and, ‘ready for a change’ moved here permanently the following year. Initially, she found work with the European Foundation for Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurobond) and inDublin magazine but her real interest was in social and political causes. This stemmed from the 11 years she spent working previously in Pesaro, Italy, with Massimo Dolcini for the trade unions and the political movements of the left. As she says of the time, “We were very active politically, doing real Robin Hood-type stuff.”

It was through Mary Elizabeth Burke Kennedy that Jole met Charlie. However, he remembers it differently. “I began to see these posters, for theatre and things that I should have been covering. The printer would show me posters and say ‘here, Charlie, look at this. It’s Jole Bortoli, she’s good isn’t she? She’s better than you!’” (He would later found out that they had been saying the same to her!).

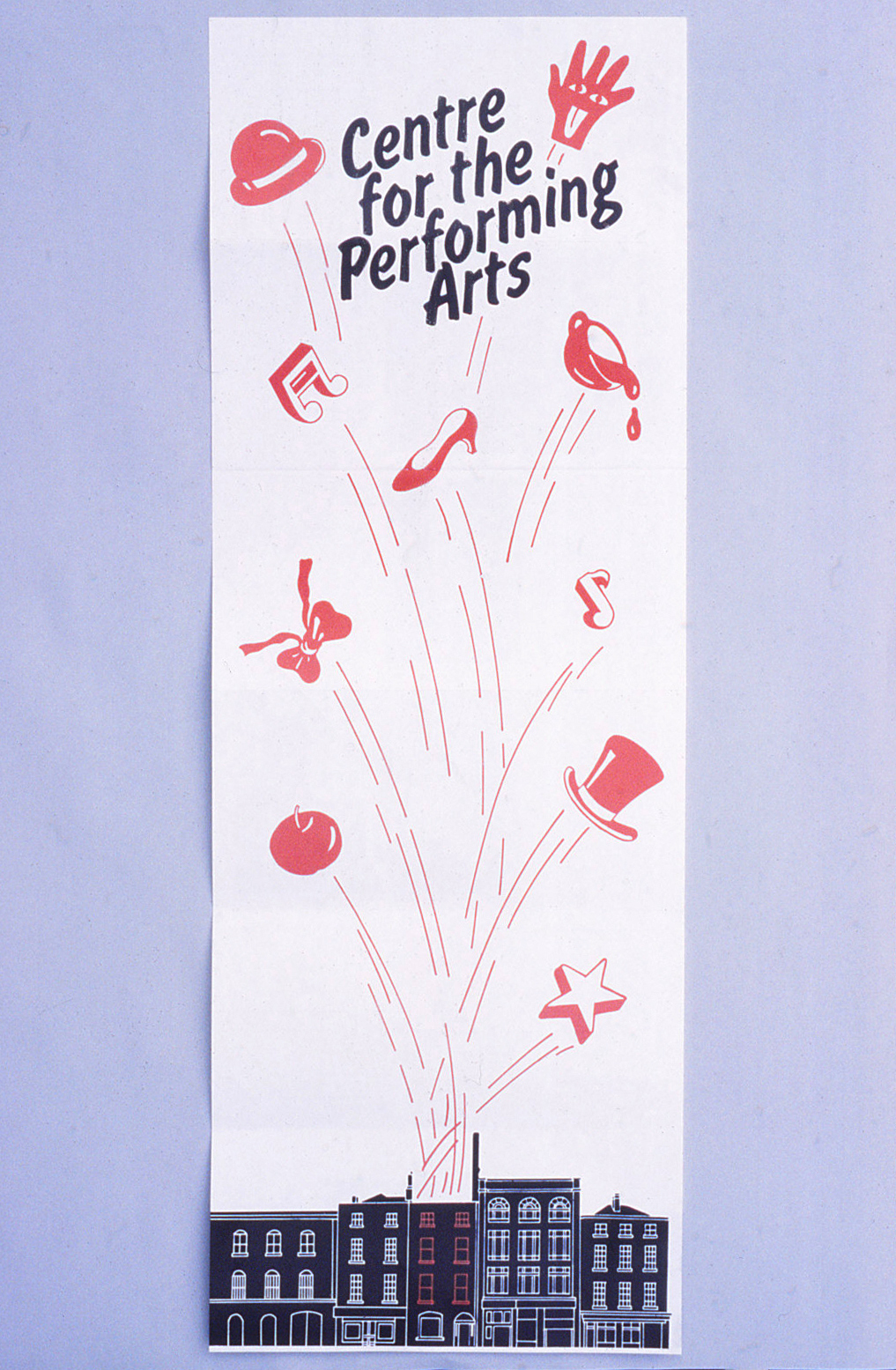

At that point, Charlie was working with Declan Buckley out of the Grapevine Arts Centre (later City Arts Centre) as the design company Flying Colours. “We were doing graphic design for the centre and then began to get work for the arts sector and music industry. It was a confluence of circumstances, where legal street postering was beginning to happen for the first time. We had the city as a canvas, which changed everything for design overnight. We were the first out there and we had nothing to lose. In design terms, there was very little else around and the real estate was there to occupy. Then you had the arts community, who had a creative sensibility and were looking for something unique and different.”

The legalisation of the street posters brought a much-needed injection of colour to the grey streets of recession-soaked Dublin and, before long, Jole and Charlie began to notice each other’s work. Jole remembers, “There weren’t many posters on the walls and then I realised they were in pubs. In Italy, you saw everything on the streets. When I started seeing Charlie’s posters around, I contacted him.”

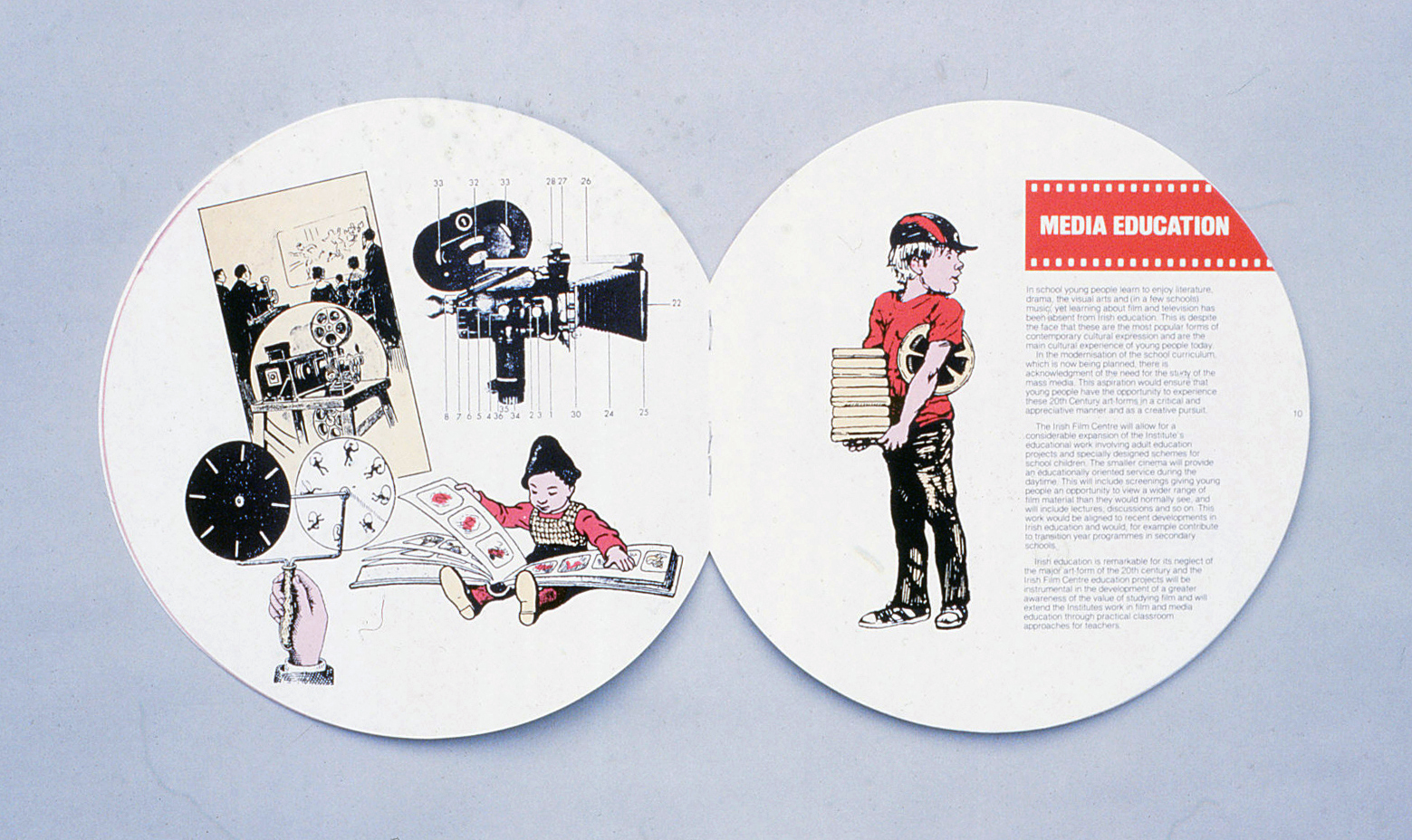

In 1985, Declan left Grapevine to work in San Francisco with the Public Media Center, leaving Charlie free to form a new partnership. He had been asked to design promotional material for the newly-named City Arts Centre to raise money to buy a building along the Quays in Dublin. “I needed some help and thought it would be a good way of seeing if Jole and I got on. So I contacted her and we worked together on a brochure, which was one of the best things we have ever done. It was silk screen-printed and was very visual and illustrated. Then we worked on another one for the Irish Film Institute.”

From that, Charlie and Jole, along with Giancarlo Ramaioli, set up Graphiconies - they coined the name to reflect their backgrounds “a kind of Irish-Italian circus design family,” as Charlie put it. Not long after they started, however, Charlie was offered a position at Public Media Center in San Francisco for 18 months. “They were doing issue-related projects, working with NGOs, charities, political movements, women’s rights and farmers. They were about influencing the agenda.”

Initially, after Charlie left, Jole and Giancarlo found it tough to get around both the language and culture barriers. Jole explains, “I had very little English and even a phone call was a problem. The culture was very different. First of all, to adjust to the Irish mentality - I would talk to a client and they would say, ‘I will ring you back tomorrow’ and they never would. Also, in Italy - probably because it was the cultural sector - they looked at the designer as expert. I found it difficult in Ireland because it was like going backwards. The other thing is, Italians are so much more direct, blunt sometimes, while the Irish were more polite. They didn’t want to say no so they’d say ‘yes that’s great' and phone you the following day and say ‘we’ve changed our mind’. That was the most difficult thing but then, slowly, I learned to love it.”

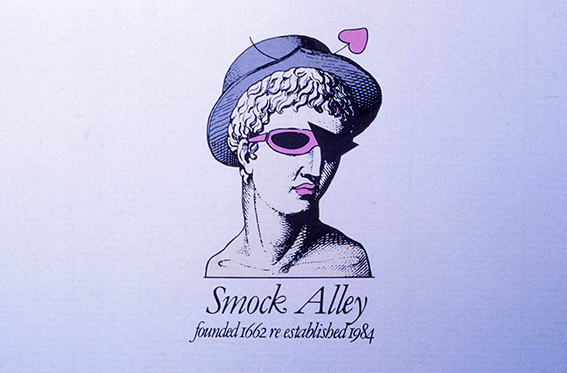

In the mid-eighties, Ireland was witnessing huge social, economic, cultural change and Graphiconies began to carve a niche in the arts sector, producing work for clients like the Arts Council, Dublin Theatre Festival and Rough Magic. As Charlie puts it, “Nobody was doing work like it. It was really design-led and there wasn’t a style, apart from it being unapologetic - some of it was illustrated, some flat shapes, loads of typography. Some of the arts clients were tough; theatre directors could have a very particular view on something and I’d do all-nighters on a poster and get 100 quid for it. I would design their programme and build in a 3D model of the set, which people could cut out and fold up. It was all about innovation and changing things a bit”.

There was never any question of working in the commerical sector, though. “It’s not that we were brave,”Jole admits. “We were ignorant. Ignorant of that sector and we just had the passion for what we wanted to do.” She recalls a chance conversation in Galway, where the uniqueness was pointed out to them, “This guy said, ‘Oh, you Graphiconies, you really have a nice niche.' I said, 'Well, nobody gave it to us, we just made it. It came out of our own interests: where we wanted to work and who we wanted to work with.' He said, ‘Aren’t you lucky?’ and we said, ‘No.' In that sense, we were different, we were apart.”

The agency took on new staff: John Sutton, who Charlie had known through Grapevine came on as studio manager, while designer Brendan Foreman, who had worked for the Abbey Theatre and the Peacock, also joined the team.

Besides the work, the agency became renowned for the Christmas party they threw each year in Mother Redcaps in Dublin's city centre. Jole and Giancarlo would cook authentic Italian dishes, while Charlie would provide the entertainment, with theatre, comedy, bands, walkabouts and musicians. The only rule was that you had to be a client in that year. “We often joked that some clients came along in October just to be part of it.” Each year, the event got more and more elaborate and often the entire marketing budget was spent on the infamous party.

Charlie’s time with the Public Media Center in San Francisco had influenced him hugely and he began to push for a change in the company’s direction. “I had grown in terms of my political awareness over those years. We had loads of lovely design and it was all very exciting and satisfying in one way but what difference were we making to the national debate? We wanted to do stuff that would affect more change. We could use our talents and skills more strategically and you couldn’t ignore all the issues happening in Ireland at the time,” he explains.

“We started looking for that kind of work and it began to come our way because there were a lot of amendments to the Irish constitution. People would come to us and say, ‘I want a poster or flyer’ and, whereas before we would ask ‘do you want it A2 or A3?’, now we were asking why do you want a poster, who are you trying to reach and is that the right platform to use?’ We began to get into those conversations and it was politicised and about changing society, how a graphic designer can create strategic communications?”

This change in focus also meant a change in name - Graphiconies was seen as “too light and cultural” for what they wanted to do next, whereas Public Communications Centre (PCC) was far more direct. This choice of name, Charlie admits, was influenced by his time in San Francisco but, for Jole, the new name didn’t have enough magic. “But I recognised that you needed to be taken seriously,” she says, adding that while she had worked in the political and social sphere in Italy, she always saw graphic design as “complete creativity”. She states, “Marrying the two didn’t really work out for me; letting go of all that creativity was really hard.”

In 1995, Martin Drury asked Jole to design the visual identity for The Ark, a cultural centre for children, based in Temple Bar and, up until 2002, she produced all the promotional material. As she puts it, “I realised that that’s what I wanted to do. My saviour was The Ark.” This led to her decision in 2002 to leave PCC and set up Art To Heart, where she works as a facilitator, running visual art programmes for adults and children.

While they no longer work together they remain friends. Jole reflects, “I think the production of images has become much more globalised now. When I was in Italy, you recognised Swiss graphics, Polish graphics, American graphics and so on. Now that’s all gone. Another change I notice when I visit Persuasion Republic is that, gradually, the area where things were done by hand started moving to the side and has eventually disappeared. It was a studio before; now it’s an office. It would be interesting to see, in the years to come, if there is a reaction like there is in other fields - vinyl is coming back, for instance. There is a need, I believe, a human need, to create something with your hands.”

Charlie, meanwhile, remains infatuated with design. “I still love the process. It’s all about that really hard work but it's also about the passion, spark, joy and excitement of it. Trying to hold onto that is hard, like when it's 2am and you’re still fumbling around, but that’s what you have to do and that’s when great work happens. Now, sometimes, it happens by accident or it just comes quickly and you go ‘oh fuck, yes’!”

During the noughties, PCC made a significant impact on the social and political landscape in Ireland. “We worked on a lot of the major campaigns over the years, leading charities and NGOs, and we thought we could raise funding and could get grant aid to run our own campaigns but that didn’t work,” Charlie says. In 2012, he and John Sutton made the decision to become Persuasion Republic. The task now, as he sees it, is to create engaging campaigns – although many of the challenges are still the same. “Ultimately, it still is a design problem. It’s a message problem and it’s an idea problem. Those things are still there and they are just as valid as ever.”