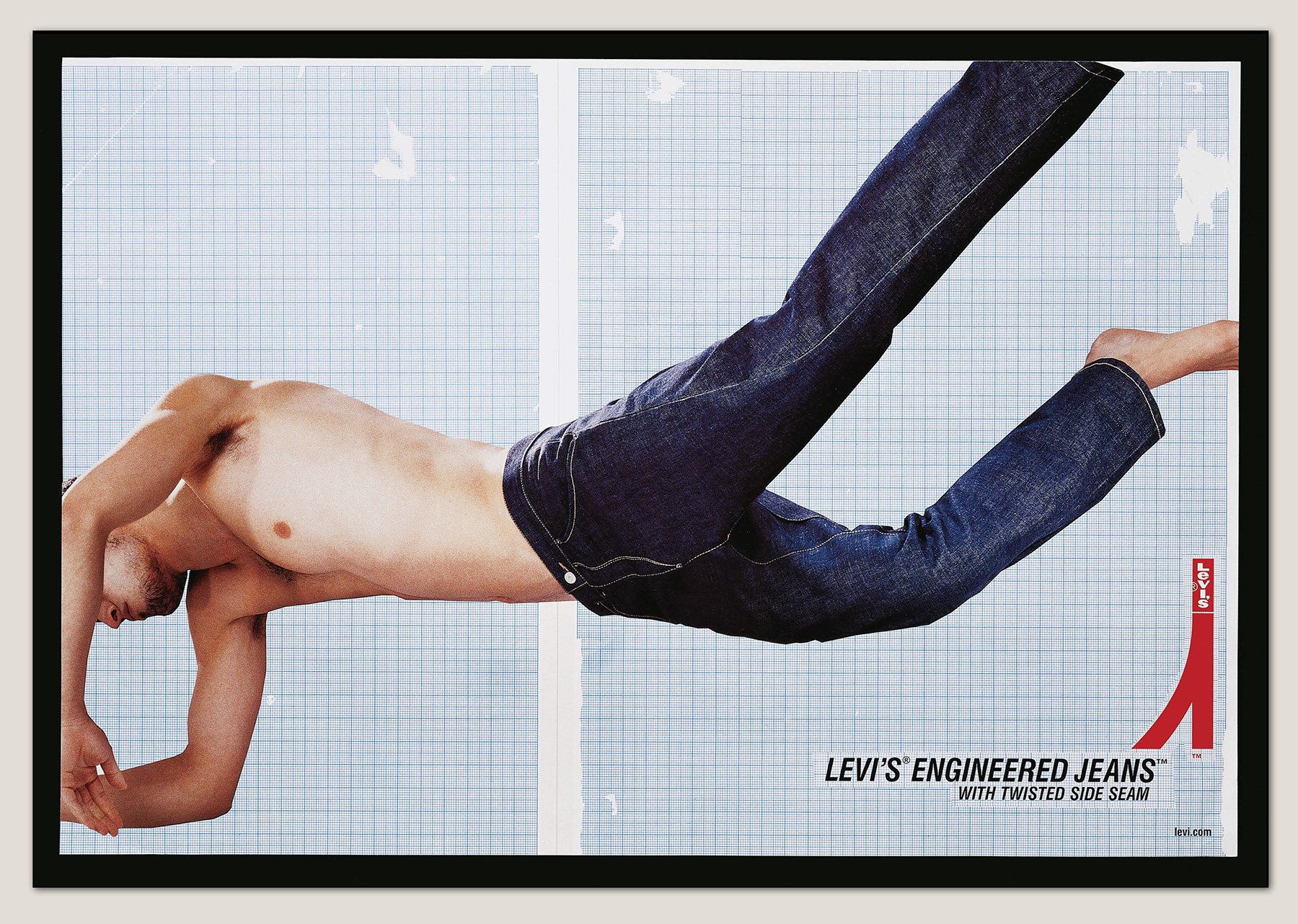

For the last 25 years, Alan Aboud has worked extensively with innovative fashion, beauty, fragrance and lifestyle brands, including Paul Smith, Zara, Levi's, H&M, River Island and Neal's Yard Remedies. Last month, Eamon Spelman talked to him about his work for Paul Smith and, during that interview, he spoke about, amongst other things, his working practice. In the following piece, he gives an honest account of his work and how, after many years in the business, he is not resting on past achievements but instead searching out new challenges and opportunities.

At college, there were no business elements integrated into the course curriculum so when we started out, we had no business plan, but we were lucky and things kept rolling. For 26 years, work just came to us, which is probably not a good idea - it's only in the last two years that we have actively being going out to get new business. With the benefit of hindsight, it is never a good idea to throw all your eggs into one basket and now we are trying to pull back and be a bit more ‘democratic’, both with the amount and kinds of clients that we work with. I don’t have any regrets about setting up a business but I have got a few thoughts about how I could have done things a bit better, in terms of strategy, for myself. You spend your life failing in this business and thinking, ‘why did I do it for nothing?’

I once went to a talk with Neville Brody and one of the things he said was, ‘work for someone else, make mistakes and let them pay for it.’ There is a certain rationale to that but, today, people don’t think twice about starting out on their own. They have a predisposition to not be bothered about going through the tough times that are often part of having your own business.

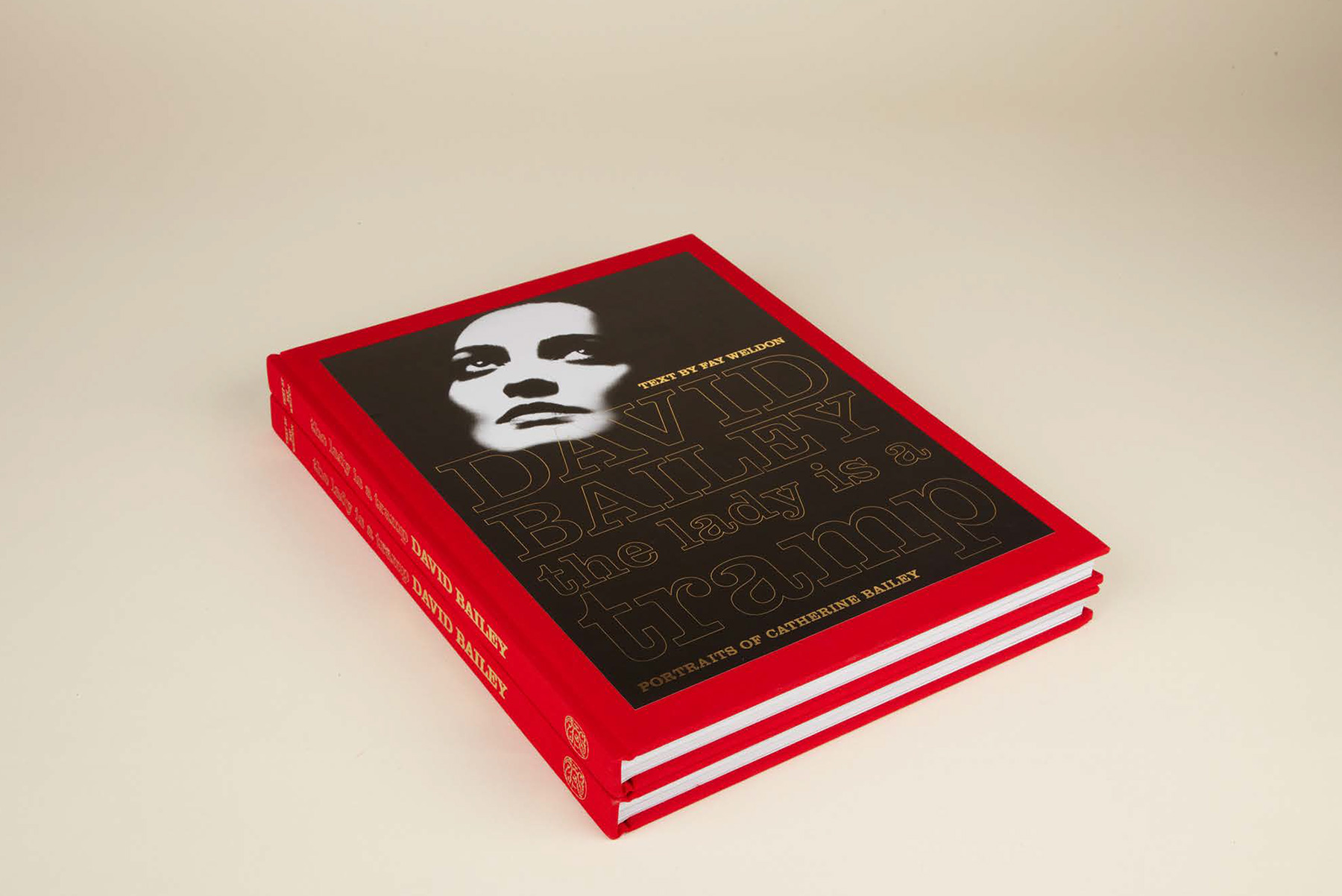

We have never been pigeon-holed, except possibly in fashion, with Paul [Smith], but now we do a lot of work with advertising agencies, who bring us in to collaborate on projects. We work directly with clients in all sorts of different ways, which fluctuate from graphic design to art direction, and we have a two-year book project that we are currently working on with an American company. At the same time, we are still doing fashion projects. So it’s a mixture between being graphic designers, creative directors and art directors.

The more successful you are, the less time you have to design. Work becomes all about getting new business and making presentations. That’s what happens unless you make a specific decision to remain a designer, first and foremost. There is a friend of mine, the designer Jonathan Barnbrook, who is very principled in what he does and how he does it; I'm not saying I'm not [principled] but he has a very political outlook on things. He has the same studio set up for 25 years and a couple or assistants working for him. He’s designing every day, whereas I'm not.

People ask what I do and I say, apart from idea generation, team construction: pulling together the talent and then being the catalyst for that talent to solve the problem collectively for a client. With any project we take on, I have to think about added value in terms of what we can do that’s different to what other people would do. My goal is to try and find clients that will give us the problem and allow us to solve the problem. I had a meeting with someone this morning and they asked ‘what can you bring to the table’ and I said ‘what we can bring to the table is ideas’. It sounds simplistic but that’s all we are about. I think as long as you can still keep coming up with ideas, you should be able to get a job. But it’s a constant fear that the ideas will run out. It’s such a youth-oriented business nowadays. Then I look back at what I would perceive as the great designers, the likes of Saul Bass, who were working into their 80s. But yes, you do have a fear that you won’t get another project.

Twenty years ago, the goal was to get your work into design publications like Creative Review, Eye, Design Week or Graphics International (which later became Grafik) and, when you could afford it, try to enter the D&AD in order to raise your profile. Now, with social media, you can create your own news-worthiness and push it out there. It’s more democratic in terms of putting your creative work out there - you don’t have to have a degree anymore, you don’t even have to have a camera. It’s a different playing field.

I think people are realising they have to do something different because anyone thinks they can do a fashion shoot. The buzz word at the moment is ‘earned media’ and clients are saying ‘we want our customers and our supporters to publicise us through social media’. What a lot of people are missing is the fact that, unless they give their support and their customers the content to arm themselves, then it’s not going to work. A lot of people think ‘let’s just post this picture of our new pair of shoes that are out and I'm sure all our followers will like it.’ There has to be something original.

I think it is really important to have an understanding of data. We do some work for Manchester United and, recently, I was in Hong Kong at their partner’s conference. It’s a three-day event, where sponsors come over, there are talks and a cross-pollination of ideas and support. One of these talks was from the director of football development about how they are collecting digital information to understand the performance of players. They are accumulating tons of information and are talking to people like Chevrolet, who are experts in the field, and are advising them as to how to get the best from this data. It goes back to people like the general manager of Team Sky, Dave Brailsford, and what he calls incremental gains. He says the principle came from the idea that, if you broke down everything you could think of that goes into riding a bike and then improved each of those things by 1%, you’d get a significant increase when you put them all together.

It’s not all about just saying ‘we are going to do better’; it’s about looking at making this little part of the whole process a tiny bit better and then another bit. It’s that kind of thing in the design industry - I think it’s quite exciting. We've got so much information and we need to understand how that can influence our ideas. The course of design is impetuous and our influences are everywhere, from going to the cinema to going to a football match or whatever. But, in this day and age, you need some kind of mathematical nuance to put all those things into context.