My experience of design in Ireland is impossible to analyse without considering my background. One and the other are inextricably linked as one formed my views of the other, and both influenced my career as a designer over the past 30 years.

Brief synopsis of a life of confusion

As it’s pretty obvious from my name, I’m not from Kerry. I’m 100% Italian genetically speaking but, that’s about where my Italian side ends, if you discount my love of strong espresso and food. My childhood and formative years were spent in a country at the opposite scale of cultural experience: Switzerland. My family moved there when I was four years old, young enough to forget about any Italian influence and become a Swiss. The next twelve years were spent growing up, moving around, speaking three different languages daily, German at school, Swiss-German with friends, Italian at home. Two opposing cultural forces—Swiss and Italian— tugging at my every action and thought. Talk about confusion!

When I turned seventeen my parents decided to move us to France. Just in case I wasn’t confused enough, I had to add a dash of Gallic je-ne-sais-quoi and the French language to the equation.

After a five year Visual Communication degree in France (really an advertising course), I decided to move back to my roots—errr, that would be the Swiss roots—and complete a further ‘diploma’ in poster design. Another two years. Those two years, however, were pivotal in my design education as they eradicated any sort of Gallic influence (awful type, dubious visuals), embraced my French sense of photography, and utterly changed my outlook on graphic design. Lecturers in Switzerland even demanded I swear allegiance to either Helvetica or Univers. No, I won’t tell you which I chose.

Monocellular Design Brain, MDB

For those two extra years of design education I did nothing else other than designing posters for cultural institutions and events. My entire life centered around design, from the moment I woke right up to the moment I fell asleep, and probably while I slept too. It was an intense design education, making sure we would never see the world in any way other than as designers. During the second and final year, I worked in one of the best design studios in Lausanne, Les Ateliers du Nord, designing posters for real clients, and occasionally photography books and logos. Simultaneously I was working on my final college project, an identity for a food shop—Italian of course. I may have been confused and troubled in terms of my roots and identity, but I certainly knew what food I liked!

Pivotal Event —sort of design related

Previous to my escape back to Switzerland from France, I had met for the first time my then future Irish partner while travelling around Italy. Communication was something of a challenge. We didn’t share the same language, nor even the same landmass. But, we persisted, using lots of drawings, gestures and mime—visual communication came into its own for both of us! Then, in the Summer ’83 I had the great idea to come to Ireland and to apply to Kilkenny Design Workshops for a summer internship and to spend time with her. Maybe not so smart, as she was working in Dublin and I was in Kilkenny, and not speaking a word of English. I did have the vague notion of learning language number five somehow. It took me a while and a lot of Irish Times reading and TV watching before I could start making sense of English and start communicating with the people around me. But again, visual communication was very useful, as designers really ‘speak’ the same language everywhere. I had a great time, and I was even considered exotic then, being the first Italian at KDW ever! So ‘exotic’ in fact, that KDW paraded me in front of the visiting Italian president, who wanted to know if I got enough pasta to eat. Of course, being a fake Italian, I had absolutely no idea who he was.

Culture clash

One thing that struck me then was the lack of poster display stands in the streets. Didn’t every country have these?? Very surprising realisation for a poster designer.

Vandalism? Err, nooo we do not have that in Switzerland. So how do you communicate cultural information to people??

(I never really found a satisfactory answer to that question. I suspect cultural institutions didn’t communicate.)

Deportation

After my three month residency at KDW, I returned to Switzerland to finish my last year of college and continue working at the design studio. While at the studio, I discovered that I couldn’t stay in Switzerland once I graduated. I wasn’t a Swiss national and I didn’t have a permanent job with the proper paperwork to allow me to stay there legally beyond my study time. The realisation that I couldn’t stay in the country I grew up in, and being told I had to leave, was a considerable shock. So, in desperation and with no other contacts, I wrote back to KDW and asked if they had a job. They did, and they offered it to me! WOW. Great, problem solved, we’re going to Ireland.

Cultural adjustments

1984. Not the George Orwell novel, although at times it felt like it. The non-conformist experience of living in sin was the reason my partner and I got turfed out of a flat for being an unmarried couple. Deciding as a form of protest, not to get married. Then getting a strange phone call at work from our building society manager asking us to get a letter from a priest to say we WOULD be getting married so we could get our first mortgage. Strange times...

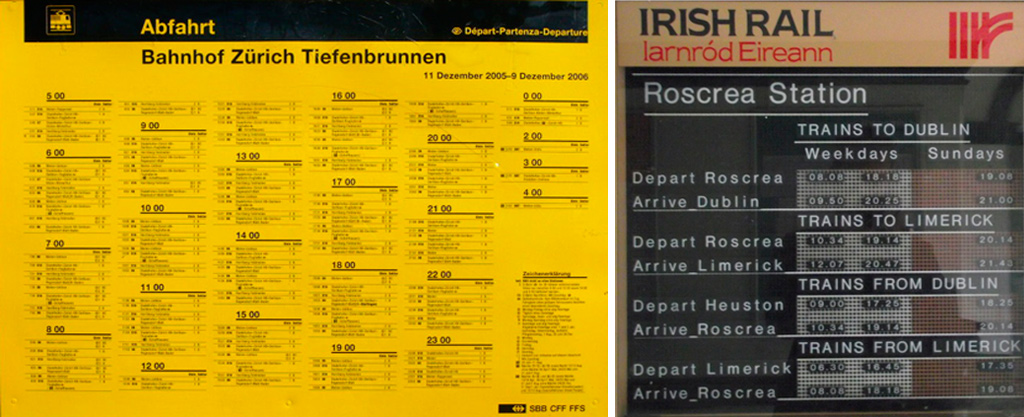

I came from a design country where trains ran every ten minutes to every minor town in the vicinity, every 30 minutes to every major city in the country, and the timetables actually meant something. They were designed that way, both in system and visually. Buses appeared when they were supposed to, according to timetables, yes. Cities worked and had very regulated systems. Everything was a system, controlled and efficient. I’m not making a judgement on the merits or horror of such places, but certainly living there didn’t require an effort. Efforts were demanded when working. I had to adjust to life in Ireland.

Food culture

Kilkenny in 1984 had one shop that sold four different types of wine, some unmentionable German brands that were close to honey, and one Italian which was drinkable. Food stuffs—another eye opener. Red cheddar?? Red lemonade???? What? Where’s the Brie and the Parmesan! Olive oil? Is it for your ears? Go to the chemist.

Daily realities

Looking for somewhere to live:

Ehm, where’s the radiators?!?!? (me)

HAHAHAHA. Use that. (Estate Agent):

What?

That, a fire.

A F I R E !?!?! You heat with COAL??

...and peat briquettes.

How Industrial Revolution!

Going out to eat:

Hey, we go have some Italian food, there’s a chipper around the corner. (Friend)

A what? (me)

Chipper, fish and chips.

What’s that? We don’t have that in Italy.

Oh, and by the way, what’s with the red check tablecloth and candles in bottles?? We stopped doing that about 30 years ago, and even then we only had it in tourist places. A sure sign for Italians to avoid such establishments.

Espresso anywhere? (me)

HAHAHAHA! Tea, pal, with milk, or something Swiss, Nescafé!

Gross.

You get the idea. There was a certain culture clash dictated by daily design expectations from my side, utter incomprehension on the other. My ordered and designed everyday living was turned upside down. The horror was complete when I spotted American Uncial on some shopfronts. That was even worse than some French shopfront typography!

Down to Design

When it came to design work in my early days in Ireland, things were a little different than now, and a LOT different from where I came from then. No poster culture to speak of, identities were at an early stage, general graphic design standards were of a sort best described as ‘in progress’. There were exceptions of course, and it turned out that most originated in KDW and from other luminaries in Dublin. That fact did have a sort of reassuring side to it as it showed that there was a lot of work to be done, and scope to develop things, and I was obviously in the right place to do so at Kilkenny Design Workshops. It was exciting, it was new, it was pioneering even! The first job I was assigned to was to assist one of the senior designers to design forms for the post office. Perfect, at least my Swiss background could be of use. Bliss. Designing other things such as a logo for Rossan, a knitwear company (still in use today), and some work for Bord na Mona (yes yes, the same turf and briquette people!), helped create diversity. I was in my element, learning new skills and solving new design problems. It wasn’t posters, but it was good.

Next, KDW gave me a BIG job to do. The corporate identity manual for An Post. Keep in mind, this was a time before computers had invaded our profession, and things were still done by hand using scalpels and Spraymount, the same scalpels surgeons use. Type was specified and set in rolls of paper, not unlike long thin rolls of wallpaper or borders. One had to cut them up and paste them down with surgical precision on sheets of card with a grid printed in non-repro blue. I had to design an identity manual, with no prior experience of such a beast, and design everything that went into it, each and every application. What a job! Brilliant. A real case of using analytical skills combined with Swiss organisational brainpower! It took a year to complete. Then the client vanished for three months only to return with the news that they had decided to change the corporate font. Another 3 months of work. I was also designing other things, and doing little jobs on the side. A few ‘posters’ mostly A3 size to be displayed in shop windows (sigh).

Once that Corporate Identity manual for An Post project was complete, I moved on to other projects, until the Ulster Weavers Identity manual landed on my desk, and then the GEA one too. I had become an expert, it seems. They weren’t the first manuals ever in the country, but they certainly did form a body of work that was rather extensive and important.

Dawn of Technology and Design

By then, design work was being produced extensively in Dublin by great design studios (Design Works, Design factory, Flying Colours, Graphiconies, to name just a few), and advertising agencies continued their design output too of course as they had done for some time. Design in Ireland started to become more visible. Awareness might not have been at a very high level both in the public and business sector, but things started to get noticed, and the value and merit of design was making an impact.

By 1986 I had access to one of the first Macintosh systems in the country, and could explore the very new possibilities of desktop publishing as it was called then. Needless to say, that system was in its infancy and wasn’t really that useful for traditional design work as we knew it. However, we did experiment with it and seeing work generated on computers by April Greimann, Neville Brody and others in those days was amazing and inspiring! A new world had started.

Sadly just at that time, Kilkenny Design Workshops closed down in the late 80s. One good aspect of that event was that designers from KDW had scattered around the country and contributed to the design scene in Ireland on a geographically wider scale. Dublin-based design studios also became more and more prominent and design became more and more visible. By then I had also moved on and was designing for my own clients, mostly identities and promotional literature, as well as information design for clients like Nicholas Mosse Pottery, Jerpoint Glass, Ballymaloe Cookery School and others, to improve their communication through clarity.

Design by then had started to change in Ireland, with more and more designers active and a greater exposure to the international design scene. Historically, and simplistically put, there has always been a certain amount of influences on Irish design from various other countries and traditions. Kilkenny Design was very much Scandinavian in feel, but also had strong Irish roots. The senior graphic designers like Tony O’Hanlon and Damien Harrington were educated in London and Holland respectively, and their work created a certain style of work at KDW which was more international. Design magazines and journals had always been a strong formative factor too.

Coming of age

Much later on when the internet appeared and the dissemination of information became even more widespread and easier to achieve, a globalisation of design was inevitable. This is more or less what we see now. The trends I can see still tend to have certain traditional traits following certain design principles that were set out in the last century. The Swiss Style is still strong, as is the Anglo Saxon influence from the UK. Visually, I tend to think that Irish design came of age when influences from outside were already strong, and a specific visual vocabulary never really developed. An aspect of Irish design which I think is characteristic is the Irish use of the English language with it’s play on words and its sense of humour. Design has certainly developed in the past 30 years and is now at a stage of maturity and confidence. The ‘old guard’ designers are still active and a new generation of designers formed in the age of Macs and the internet have added a lively and playful side to the design scene. This scene is now one of assured and innovative play and experimentation, combined with a sense of discovery which forms part of any vibrant design culture. Ireland has in my view now reached a level of design infiltration in everyday life that is pervasive and accepted, if not expected yet. The next phase will be a general expectation of everyday life being influenced by design at every level. This isn’t Switzerland, but the creativity and self-reliance on doing things ‘in our own way’ does show the potential of what’s to come.

As for me, I consider myself a Swiss designer, with a love of the English language and it’s Irish use, and a style that mixes a certain Swiss style with some Anglo Saxon influences. As my brother (also a graphic designer) once described it, ‘you’re very English—pictorial in your design work—with a weird Swiss typographic and analytical slant’. I guess I’m continuing my tradition of mixing cultures and taking from them, and I’m glad I’m living here to practice them without constraints and historical baggage. Thirty years on, I’m still passionate about design and in a changed society I think design skills are more valuable than ever. Design skills are being used as a means of improving the quality of life in a financially compromised environment. The example of coworking spaces such as Fumbally Exchange demonstrate what can be achieved when design and other creative disciplines come together for the benefit of local communities. My involvement in Fumbally Exchange in Waterford marks a new departure for me with the opportunity of using my skills as a designer for a more direct social purpose.